SITE GUIDE

SEARCH

REVIEWS

REVIEW ARCHIVES

ADVERTISING AT CURTAINUP

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

New Jersey

DC

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

A CurtainUp Review

The Train Driver

|

"I got some good guesses going about your world and why you stood there on the railway line waiting for me and my train. One of my guesses is that I think it’s all about Hope. You know what I mean . . . Hope! . . . hoping good things are going to happen to you, that tomorrow is going to be better than today which was terrible. And there you have it. "— Roelf (walking alone among the graves)

|

Ritchie Coster

(Photo: Richard Termine) |

That Athol Fugard, South Africa’s venerable, highly lauded playwright, is a helluva storyteller is re-affirmed by The Train Driver, among this eighty-year-old’s more recent and arguably best plays. The commitment of the Signature Theater to provide theater-goers with an opportunity to see a selection of plays by a notable group of “playwrights in residency” is a commendable mission. How great it is to be able to get even a limited overview of Fugard’s work from an earlier time to the present, without taking a college course. This provides an easy access to a perspective as well as a fuller appreciation for him, let alone the essential rewards of the theatrical experience.

Actually I shouldn’t be using the word easy to describe what it feels like to be caught in the conflicted emotional turbulence that fuels so many of the characters that have sprung from Fugard’s mind over the past fifty years. For those of us who have been stirred again and again by his plays, whether they are the ones prompted by the very specific conditions that existed under apartheid, or the later ones in which the human experience in the new Africa is revealed (as is this one), they comprise a remarkable canon by a master playwright.

While Fugard’s earliest plays like Blood Knot< and My Children My Africa, are set during the time of apartheid, and produced at Signature last season, The Train Driver is based on a true newspaper account of a tragic incident that got Fugard’s attention. Apparently a black woman living in a squalid squatter camp became so despondent that she threw herself and her infant on the tracks in front of an on-coming train.

Simon’s narrative segues into the story as a noticeably unsettled middle-aged Roelf enters the littered grounds of the cemetery. Scruffy and exhausted, he has questions for Simon, the resident grave-digger whose job it is to bury “the nameless ones,” those who died with the same anonymity that a disassociated society and economic conditions had ascribed to them. When night falls, he quiets the barking of roaming dogs by singing to the spirits of the dead. Roelf, the driver of the train that killed the woman and her child, is on the verge of losing his sanity, his job and his family. Since the incident, he has been consumed with feelings of guilt and desperate need to seek redemption by seeking out the grave where the woman and child have been buried.

A relentless search has led him to this unkempt cemetery where the refuse and rubble is used, as Simon explains, symbolically for flowers. Although Roelf is appalled by what he sees, he is primarily haunted by the memory of the eyes and the face of the woman just before she was “pulverized” beneath the train. Reliving the incident has also made him increasingly aware of the plight of those reduced to poverty and the indifference of those who could affect a change.

Despite Simon’s warning of a band of knife-carrying, life-threatening youths, Roelf accepts the reluctant and wary Simon’s invitation to stay with him in his spartan hovel, sleep on the floor and share his modest meals…warmed by a single candle. Although Simon tries to convince Roelf of the futility of his search, their conversations are mostly one-sided with Roelf doing most of the talking, and Simon hoping that this frenzied soul will leave before he is discovered.

If acting can ever be called authentic then it can be applied to both Coster, as the self-absorbed, consumed-by-guilt intruder and to Brown, as the powerless host whose hand-to-mouth, day-to-day existence may also be in jeopardy. Through both these fine performances we also get indications of the underlying, distressing and perpetuating disconnect between the races, the festering conscience of a generation of whites destined to harbor the pain of lost moral authority, and the lingering plight of their victims, the impoverished blacks of South Africa. Fugard doesn’t disappoint us with a climactic jolt that brings his play to an unexpected conclusion.

With Fugard directing his own play, I suspect that he may be less likely to punctuate a key scene than he is to indulge it. But this is a play that resonates on a dramatic frequency that is uniquely Fugard’s. Although the play takes place over three days and nights, time does seem to stand still on occasions for Roelf and Simon, as it is probably meant to considering the inherent passivity that exists in this sorrowful place where penitence may be the only hope. In this era of sound bites and visual trickery (kudos, however, to Stephen Strawbridge’s dusk-to-dawn lighting) Fugard’s unhurried story-telling style may strike some as a bit retro, but for those willing to listen carefully and feel deeply, The Train Driver will be a rewarding experience.

Fugard dedicates this play to: Pumla Lolwana and her three children — Lindani, Andile and Sesanda—- who died on the railway tracks between Philippi and Nyanga on The Cape Flats on Friday December 8th 2000.

|

The Train Driver By Athol Fugard Directed by Athol Fugard Cast: Leon Addison Brown (Simon Hanabe), Ritchie Coster (Roelf Visagie) Scenic Design: Christopher H. Barreca Costume Design: Susan Hilferty Lighting Design: Stephen Strawbridge Sound Design: Brett Jarvis Original Music: Doug Wieselman Running Time: 90 minutes no intermission The Romulus Linney Theatre (in the Pershing Square Signature Center), 480 West 42nd Street 212-244-7529 Tickets: $25.00 Performances: Tuesday through Friday at 7:30; Wednesday at 2 PM; Sunday at 2 PM and 7:30 PM. From: 08/14/12 Opened: 09/09/12 Ends: 09/23/12 Review by Simon Saltzman based on performance 09/07/12 |

|

REVIEW FEEDBACK Highlight one of the responses below and click "copy" or"CTRL+C"

Paste the highlighted text into the subject line (CTRL+ V): Feel free to add detailed comments in the body of the email. . .also the names and emails of any friends to whom you'd like us to forward a copy of this review. Visit Curtainup's Blog Annex For a feed to reviews and features as they are posted add http://curtainupnewlinks.blogspot.com to your reader Curtainup at Facebook . . . Curtainup at Twitter Subscribe to our FREE email updates: E-mail: esommer@curtainup.comesommer@curtainup.com put SUBSCRIBE CURTAINUP EMAIL UPDATE in the subject line and your full name and email address in the body of the message. If you can spare a minute, tell us how you came to CurtainUp and from what part of the country. |

Slings & Arrows- view 1st episode free

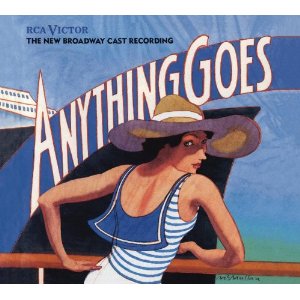

Anything Goes Cast Recording

Anything Goes Cast RecordingOur review of the show

Book of Mormon -CD

Book of Mormon -CDOur review of the show