SITE GUIDE

SEARCH

REVIEWS

REVIEW ARCHIVES

ADVERTISING AT CURTAINUP

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

New Jersey

DC

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

A CurtainUp Review

The Old Boy

|

"If you marry money, you earn every cent of it.".—Alison

|

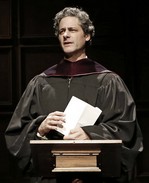

Peter Rini

(Photo:Carol Rosegg) |

Through Tennessee Williams's southern dreamers, Lillian Hellman's southern schemers, Eugene O'Neill's disheartened, boozing New Englanders, Arthur Miller's disillusioned, socio-politicized working class, and certainly through August Wilson's generations of African-Americans transiting ten decades in the USA, we have gotten very incisive perspectives of these playwrights as well as of the particular characters and worlds they parented.

One of the most distinctive dramatic chroniclers of a particular class of people is A.R. Gurney. Though perhaps never, to be acknowledged among the titans of American playwrights, Gurney has nevertheless secured himself a place as an acute observer of that distinctly American class of people — the upper-class WASP, most familiarly acknowledged as inhabitants of the USA's northeast corridor.

As we move forward into the more unprotected societal trenches of the 21st century plays like The Dining Room, The Cocktail Hour and Love Letters, appear in retrospect increasingly quaint and indeed remote. Their most keenly embedded facet is the well-bred-ocracy that governs the lives of their characters.

Rather than go into the list of Gurney's most recent plays that still feed into the notion that theirs is a vanishing world, I suspect there may, indeed, be a resurgence spurred by the increase of one percenters who appear to be relentlessly bent on re-ghetto-ing society into the haves and have-nots.

Be that as it may, The Old Boy is now being revived by the admirable Keen Company noted for declaring its dedication to "sincere" plays. Under the carefully finessed direction of Jonathan Silverstein, it is certainly an example of a sincere effort by Gurney to show the inevitable shift in the traditional WASP landscape which in this play is a private New England boarding school in the early 1990s, with some scenes in the late 1960s. Though not a great Gurney it's short, well-meaning and "sincerely" acted.

Sam (Peter Rini), a Secretary of State for Political Affairs with his eye on a run for governor, has been invited to return to the exclusive school he attended to give the commencement address. During it, he is going to announce the gift of an indoor tennis facility to be built in memory of Perry (Chris Dwan) a former student who has recently died.

Donating the funds for this is Perry's extremely wealthy mother Harriet (Laura Esterman). It's in part her grand thank you gesture to Sam, who was Perry's "old boy," the term used for upper classmen who served as both mentors and guides to new boys. Harriet is also using this as an opportunity to secure a spot for Perry's son at the school. Attending the ceremony with her is Perry's wife Alison (Marsha Dietlein Bennett) who we learn had more than a fling with Sam before her marriage to Perry. It appears that she has always harbored a hope to rekindle the old flame. What better time, after so many years apart than now?

Also present is Sam's campaign manager Bud (Cary Donaldson) who is not happy about this detour which he views as a politically detrimental decision in the light of Perry's death from AIDS (there's also a hint of suicide). Since Sam seems to have been completely unaware of Perry's out-of-the-closest escapades after his marriage to Alison, he finds himself in the middle of an easily politicized predicament. A flashback in which Sam sees how naive he was to pick up ON Perry's admission of his sexual preference is a device that is used as a bridge to understanding the brief, unlikely friendship between Sam and Perry as school buddies — with Rini playing the older and younger Sam quite convincingly, and often amusingly.

Dwan is quite good at addressing the nuances that characterize Perry's presumably conflicted personality. While it is easy to see how far off course Perry has been driven by his mother to mold him into a respectable junior member of the WASP high society, it is also easy to see where and how the play begins to veer discomfortingly off its course and away from Gurney's usually more insightful perspective of a class of people who know how and when to keep things under control and in check.

The play's most glaring flaw is dialogue that sounds like unwittingly contrived pandering to an elite breed. As noted in the script, this is a new version of the play that originally opened in 1991 at Playwrights Horizons. One has to suppose it was a good idea.

The Old Boy's modest merits continue to rest in the artfully projected mannerisms and arched decorum that define and refine his characters. This is most notable in Harriet, as played with a staunchly patrician sense of self by the excellent Esterman and in Alison, as believably played with prevailing sense of cheek and chic by the slim and blonde Bennett.

It's a reunion of sorts for Sam, Harriet and Alison; also for Dexter (Tom Riis Farrell), the school's affably still-in-the-closet Episcopal minister, who makes occasional forays into the handsomely furnished wood-paneled room of the exclusive school, nicely evoked by set designer Steven C. Kemp. The school serves as a conduit to these characters' past: Sam's shallow, homophobic youth, Harriet's denial of her son's sexuality, and Alison's not only discovering it too late but also that she was also used by the womanizing Sam as a pawn. It's all part of the prickly political and social issues, guilt-ridden memories, and unforgiving attitudes that are revealed in through the present and in flashbacks.

Oddly, the scenes in the past are undermined by being queasily naïve, almost corny. You want to wince when Perry admits he would rather be Viola in a school production of Twelfth Night than continue playing tennis, the one sport in which he is good enough to win a trophy. Another gulper is Sam trying to make a man of Perry when they have a chance to pick up some girls on the road, and then attempting to fix him up with one of his soon-to-be-discarded girl friends which is, of course, Alison. The echoes of Robert Anderson's similarly themed 1953 play about a sensitive young man's coming of age Tea and Sympathy are unmistakable.

It probably isn't important whether one buys into or not the sentiments expressed in Sam's off-the-cuff commencement speech ("I tried to make him fit in. I tried to make him act against the promptings of his own soul"). Call it his Episcopal epiphany, but it is hard to buy into the clichés that are used to define Perry almost solely through his love of theater and, even more, for opera. The special passion for La Forza del Destino is a rather obvious intimation of Perry's ill-fated life-style. I suspect that director Silverstein had more to do with selecting this unnecessary revival of The Old Boy than any inferred force of destiny.

|

The Old Boy By A.R. Gurney Directed by Jonathan Silverman Cast: Tom Riis Farrell (Dexter), Cary Donaldson (Bud), Peter Rini (Sam), Laura Esterman (Harriet), Chris Dwan (Perry), Marsha Dietlein Bennett (Alison). Scenic Design: Steven C. Kemp Costume Designer: Jennifer Paar Lighting Designer: Josh Bradford Original Music: Ryan Rumery Sound Designer: M. Florian Staab Fight Director: Calleri Casting Running Time: 1 hour 15 minutes no intermission The Clurman Theater, Theater Row, 410 West 42nd Street (212) 239 - 6200 Tickets: $62.50 Performances: Tuesday at 7pm, Wednesday - Friday at 8pm, Saturday at 2pm and 8pm, Sunday at 3pm From 02/12/13 Opened 03/05/13 Ends 03/e0/13 Review by Simon Saltzman based on performance 03/01/13 |

| REVIEW FEEDBACK Highlight one of the responses below and click "copy" or"CTRL+C"

Paste the highlighted text into the subject line (CTRL+ V): Feel free to add detailed comments in the body of the email. . .also the names and emails of any friends to whom you'd like us to forward a copy of this review. Visit Curtainup's Blog Annex For a feed to reviews and features as they are posted add http://curtainupnewlinks.blogspot.com to your reader Curtainup at Facebook . . . Curtainup at Twitter Subscribe to our FREE email updates: E-mail: esommer@curtainup.comesommer@curtainup.com put SUBSCRIBE CURTAINUP EMAIL UPDATE in the subject line and your full name and email address in the body of the message. If you can spare a minute, tell us how you came to CurtainUp and from what part of the country. |

Slings & Arrows- view 1st episode free

Anything Goes Cast Recording

Anything Goes Cast RecordingOur review of the show

Book of Mormon -CD

Book of Mormon -CDOur review of the show