SITE GUIDE

SEARCH

REVIEWS

REVIEW ARCHIVES

ADVERTISING AT CURTAINUP

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

New Jersey

DC

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

A CurtainUp Review

The Dance and the Railroad

|

" This mountain is clever. But why shouldn't it be? It's fighting for its life, like we fight for ours."— Ma

|

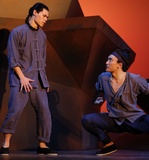

A scene from The Dance and the Railroad

(Photo: Joan Marcus) |

Though he is best-known for his Tony Award-winning play M. Butterfly, Hwang has penned a raft of other plays, librettos, screenplays, and TV movies. Chronologically, The Dance is his second play (his first was the Obie Award-winning FOB). It follow an exceedingly simple plot line: Biding time during a strike, two Chinese workers named Lone and Ma try to reconnect with their ancient traditions on a California mountaintop near the Transcontinental Railroad in June 1867.

The two men start out as virtual strangers, but a bond soon develops between them as the afternoon grows into evening, and the night stretches toward dawn. When the play opens, 21 year-old Lone is practicing Chinese opera techniques while Ma spies on him from a hidden recess in the mountain. When Ma suddenly reveals himself to Lone, and expresses his dream of being a performer, Lone first mocks him but later takes him under his artistic wing and teaches him the craft of opera. As the hours pass, Lone and Ma hone their acrobatic maneuvers, swap their life stories and dreams, and reflect on their collective yellow revolt against their white bosses.

The play made a lot of noise in New York back in 1981. Commissioned by the New Federal Theatre, it premiered at the Joseph Papp Public Theater, the second of five Hwang plays that Papp would champion. It was praised by then New York Times critic Frank Rich and was tapped as a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and nominated for a Drama Desk Award.

The current production must be taken on its own terms. Fortunately, May Adrales intelligently directs, emphasizing the themes of ethnic isolation and the struggling emergence of Asian-American identity. If the first production of The Dance brought attention to Hwang as an original voice in American theater, this revival points up how much he has increased our consciousness of Asian Americans and their not-so-easy assimilation into American culture.

If Hwang bolstered his reputation by his deft handling of the cultural divide and delighted us with his quirky humor in The Dance, he fully realized that this play would always pose problems in getting from page to stage. Since much depends on casting two Asian actors who have a special expertise in traditional Chinese dance. And, not surprisingly, finding actors with such qualifications are as rare as finding the perennial hen's teeth. Happily, this production has struck gold with two talented young performers.

Yuekun Wu plays the aptly-named Lone with astonishing virtuosity. Not only does he convincingly convey his character's arrogance, but he dances like a dervish throughout, executing the intricate dance movements with crisp panache. Ruy Iskandar, as the naive and awkward Ma, serves as a good comic foil for Lone. His physical acting is less demanding but still requires intense concentration and stamina. Iskandar's Ma wears his admiration for Lone on his sleeve, and his Spaniel-like devotion makes him very likeable. Though Wu has the heftier role, Iskandar deepens the psychological textures of the play.

Mimi Lien's minimalist set consists of geometric shapes and curves, which neatly suggest a mountaintop and its clean sweep of ridges. It's the equivalent of visual music playing out at a high altitude. Add in Jiyoun Chang's inspired lighting, Broken Chord's windy sound design and Huang Ruo's flute music, and Jennifer Moeller's traditional costumes, and you have a production that doesn't neglect to sound a discordant note now and then to keep the dramatic tension building.

The story is ostensibly about a mid-nineteenth century labor strike in California. But tucked into the dramatic underlining there's an earnest investigation into what it means to be an artist, or rather an Asian or Asian-American artist.

Hwang sometimes hammers home his points with unattractive details gleaned from Chinese lore. For example there's a pivotal scene mid-way through when Ma declares to Lone that he wants to be "an actor." Lone immediately punctures his dream by telling him a parable about three sons in a Chinese family who followed different career paths, with the first becoming a coppersmith, the second a silversmith, and the third an actor. Then Lone, with corrosive candor, tells Ma the rest of the parable, including that the mother grew so sad over her third son's acting aspirations that she "beat her head against the ground until the ground, out of pity, swallows her." Even worse, the grieving father had his flesh blown away from his bones and later strewn over tree limbs. This nightmarish story reveals Hwang's mastery of metaphor and that he feels the Chinese culture and people at a very deep level.

It's been over three decades since this 70-minute history play was first seen in New York. It still deserves some fresh applause.

|

The Dance and the Railroad Written by David Henry Hwang Directed by May Adrales Cast: Ruy Iskandar (Ma), Yuekun Wu (Lone). Sets: Mimi Lien Costumes: Jennifer Moeller Sound: Broken Chord Music: Huang Ruo Lighting: Jiyoun Chang Chinese Opera Consultant: Qian Yi Stage Manager: Cole P. Bonenberger Alice Griffin Jewel Box Theatre at The Pershing Square Signature Center, located at 480 W 42nd Street (between Ninth and Tenth Avenues). Tickets: $25 during initial run through March 17; $50 during the extension week through March 24. Phone 212/ 244-7529 or visit www.signaturetheatre.org Opening 2/25/13; closing 3/24/13. Through Monday February 25: Tues - Fri @ 7:30pm, Sat @ 8pm, Matinees @ 2pm on Sat & Sun, Opening night on February 25 @ 7:00pm. Wed, Feb 27 - Sun, Mar 3: Wed - Fri @ 7:30pm, Sat @ 8pm, Sun @ 7:30pm, Matinees @ 2pm on Wed, Sat, & Sun. Tues, March 5 - Sun, March 24: Tues - Fri & 7:30pm, Sat @ 8pm, Matinees @ 2pm on Wed, Sat, and Sun. Running time: 70 minutes with no intermission Reviewed by Deirdre Donovan based on press performance of 2/22/13 |

|

REVIEW FEEDBACK Highlight one of the responses below and click "copy" or"CTRL+C"

Paste the highlighted text into the subject line (CTRL+ V): Feel free to add detailed comments in the body of the email. . .also the names and emails of any friends to whom you'd like us to forward a copy of this review. Visit Curtainup's Blog Annex For a feed to reviews and features as they are posted add http://curtainupnewlinks.blogspot.com to your reader Curtainup at Facebook . . . Curtainup at Twitter Subscribe to our FREE email updates: E-mail: esommer@curtainup.comesommer@curtainup.com put SUBSCRIBE CURTAINUP EMAIL UPDATE in the subject line and your full name and email address in the body of the message. If you can spare a minute, tell us how you came to CurtainUp and from what part of the country. |

Slings & Arrows- view 1st episode free

Anything Goes Cast Recording

Anything Goes Cast RecordingOur review of the show

Book of Mormon -CD

Book of Mormon -CDOur review of the show