SITE GUIDE

SEARCH

REVIEWS

REVIEW ARCHIVES

ADVERTISING AT CURTAINUP

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

New Jersey

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

A CurtainUp Los Angeles Review

The Royale

By Jon Magaril

|

"Look at the dogs you're about to unleash."— Nina to Jay

|

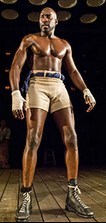

David St. Louis

(Photo credit: Craig Schwartz) |

The central figure, Jay "The Sport" Jackson, is clearly modeled on Jack Johnson, who held the title from 1908 to 1915. The search for a white boxer to unseat him was the subject of Howard Sackler's Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award-winning play The Great White Hope, which put James Earl Jones and Jane Alexander on the map more than forty-five years ago. The sprawling, naturalistic piece focused on the boxer's battles with the society a round him. Sixty actors (yes, sixty!) played approximately eighty roles to give teeming physical life to that outside world. Ramirez instead burrows inside. He wants us to know how it feels to be ringside. Even more, he wants to take us past the ropes and into the boxer's mind. Owing more to hip-hop contests than realistic enactments of fights, stylized rhythm, movement, and pungently poetic dialogue create blow after blow of sensations that pack a wallop.

On Andrew Boyce's set dominated by a wooden-planked platform, the story is told in six "rounds." The first is a fight between Jackson (David St Louis) and Fish, another African-American boxer (Desean Terry). They face us, not each other. The four other actors sit upstage in wooden chairs, also facing us. This is a timeless ritual, in which only the fittest survive.

Jackson rules as much by what he says as how he hits. This isn't just a theatrical device. Like Ali generations later, Johnson was renowned for his verbal takedowns of his opponents. But these fight sequences rattle the bones through percussive beats made by slapping hands and stamping feet (devised to galvanizing effect by Ameenah Kaplan). The ensemble evokes the primal underpinnings of a crowd and contestants united in their hunger for a show of overwhelming force.

The fighters don't use their hands to throw punches. They stomp. These moments land with pure exhilaration. Jackson wins but not as easily as he'd expected. So he does the smart thing. He hires Fish as his sparring partner. Here and throughout, Jackson doesn't let pettiness get in the way of his larger ambition. Though backed by a white promoter (Keith Szarabajka) and a black couch (Robert Gossett), the fighter calls the shots. And he's not content to be just "the world colored heavyweight champion."

Half the battle though is convincing the white title holder, now retired, to get in the ring with him. Ramirez mashes up the specifics of Johnson's first two bouts with white opponents in creating Bernard Bixby (who remains unseen). In what he assumes will be a deal-breaker, the champ demands ninety percent of the take. Jackson surprises everyone, including his own team, by signing off on it. He's got his eyes on the bigger prize.

With the bout finally scheduled, The Sport's sister Nina (Diarra Oni Kilpatrick) tries to intervene, warning about the violence that might erupt if her wins. Jackson's confident he can take care of himself. But that's not who Nina's worried about. A white mob would find black stand-ins. Is Jackson willing to accept responsibility for the collateral damage?

Nina arrives so late in the story, she seems at first to be just a mouthpiece for Ramirez to explore the larger issues of the piece. Fortunately, she's played by Kilpatrick, who gave one of the best performances of the season in the Fountain Theatre production of Tarell Alvin McCraney's In the Red and Brown Water (which was also choreographed buoyantly by Kaplan). Her vivid presence adds helpful dimension to the role.

Ultimately Ramirez makes phenomenal use of Nina in the title bout. She appears as Bixby, rattling Jackson's focus with vicious shots at his selfishness. In these moments, the stylized elements come together with the force of a one-two punch.

It's difficult to buy Jackson's sudden concern for the potential consequences of his victory. The sequence is undercut even farther by intercutting it with Fish listening to the fight at a bar, where Nina's fears ultimately come true. It makes perfect sense but because Fish has had little to do since the first scene, it feels like just that, an idea.

As with the previous production at the Kirk Douglas, The Nether, the effectiveness of a talented young playwright's work is cut short by its brevity. Fascinating elements feel thinly abstract because there's too little stage time to flesh them out.

Ramirez is, without a doubt, a comer. He's provided a stunning blueprint and Daniel Aukin has staged it brilliantly. The design and most of the performances carry a whiff of the period without an ounce of artifice. David St. Louis is every inch a champion and Desean Terry a worthy sparring partner. Lap Chi Chu's lighting and Ryan Rumery's sound design amaze with their simple ingenuity.

In the final round, The Royale wins by TKO. It's a Theatrical Knock-Out.

|

The Royale By Marco Ramirez Directed by Daniel Aukin Cast: Robert Gossett (Wynton), Diarra Oni Kilpatrick (Nina), David St. Louis (Jay), Keith Szarabajka (Max), Desean Terry (Fish) Set & costume designer: Andrew Boyce Lighting designer: Lap Chi Chu Music & sound designer: Ryan Rumery Movement and rhythm: Ameenah Kaplan Production Stage Manager: Randall K. Lum Running time: 75 minutes without intermission Runs Tuesday to Sunday through June 2 at the Kirk Douglas Theatre 9820 Washington Blvd., Culver City, CA, 90232 Reviewed by Jon Magaril |

|

REVIEW FEEDBACK Highlight one of the responses below and click "copy" or"CTRL+C"

Paste the highlighted text into the subject line (CTRL+ V): Feel free to add detailed comments in the body of the email. . .also the names and emails of any friends to whom you'd like us to forward a copy of this review. Visit Curtainup's Blog Annex For a feed to reviews and features as they are posted add http://curtainupnewlinks.blogspot.com to your reader Curtainup at Facebook . . . Curtainup at Twitter Subscribe to our FREE email updates: E-mail: esommer@curtainup.comesommer@curtainup.com put SUBSCRIBE CURTAINUP EMAIL UPDATE in the subject line and your full name and email address in the body of the message. If you can spare a minute, tell us how you came to CurtainUp and from what part of the country. |

Book of Mormon -CD

Book of Mormon -CD