SITE GUIDE

SEARCH

REVIEWS

REVIEW ARCHIVES

ADVERTISING AT CURTAINUP

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

New Jersey

DC

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

Writing for Us

A CurtainUp  London Review

London Review

London Review

London ReviewRough Crossings

|

For them, freedom is a principle. For us, it is a matter of life or death.— Thomas Peters

|

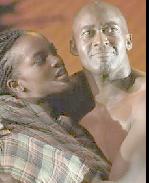

Wunmi Mosaku as Sally Peters and Patrick Robinson as Thomas Peters .

(Photo: Manuel Harlan)

|

Concentrating on less obvious figures in history (William Wilberforce, for instance, makes no appearance), the play looks at a particular slither of the history of slavery: the Sierra Leone Company and its attempt to establish the first colony for repatriated slaves towards the end of the eighteenth century. The onstage action veers between American plantation slaves escaping to fight for the British in exchange for promised freedom during the War of Independence and Georgian England, where impassioned protestors fight the legality of the slave trade. Therefore, while one scene may show Granville Sharp (Michael Matus) and his attempts to change the world with theoretical, legal arguments, morasses of documents and elderly judges, the next scene will see American slaves suffering in the midst of the unjust reality, exploited and betrayed by the British army they had risked the battlefield for.

In the second half, these two threads come together, as the former slaves, now honorary British citizens, are taken to Sierra Leone for their own land, freedom and political self-determination, under the aegis of the abolitionist Lieutenant John Clarkson (Ed Hughes). The cast are excellent and especially Patrick Robinson whose amazing voice and stature is put to good use in the part of Thomas Peters, who is both a stubborn firebrand and a principled hero.

The staging, in the talented hands of Rupert Goold is a great strength of this production. The stage floor is a single tilting disk, which is perfect for portraying a sense of sea passages, so integral to this story. Intensely evocative, the action is shot through with clever staging tricks. For example, slaves sitting crammed beneath one end of the stage angled upwards, as if on ship, or the silent, unseen presence of slaves grouped around while British abolitionists argue. Atmospheric lighting instantly recreates scenes on sea, on sun-cracked African soil, in British courts and frozen Nova Scotia plains. The music is also impressive, spanning across harpsichords, African drums and Gospel hymns.

Caryl Phillips’ adaptation has excellent pace to the writing, but the biographical focus means that it can at times feel sprawling and lacking in cohesion. Nevertheless, the strong cast and breathtaking aesthetics turn a project which could have easily been a stodgy polemic into a moving, arresting experience.

|

ROUGH CROSSINGS

By Simon Schama Adapted for the stage by Caryl Phillips Directed by Rupert Goold With: Peter Bankole, Miranda Colchester, Peter De Jersey, Ian Drysdale, Dave Fishley, Andy Frame, Rob Hastie, Dawn Hope, Ed Hughes, Mark Jax, Jessica Lloyd, Michael Matus, Wunmi Mosaku, Ben Okafor, Patrick Robinson, Daniel Williams Design: Laura Hopkins Lighting: Paul Pyant Composer and Sound Design: Adam Cork Video and Projection Design: Lorna Heavey Movement Director: Liz Ranken Running time: Two hours 50 minutes with one interval A Lyric Hammersmith, Headlong Theatre, Birmingham Repertory Theatre Company, Liverpool Everyman and Playhouse and West Yorkshire Playhouse Co-production. Box Office: 08700 500 511 Booking to 13th October 2007 Reviewed by Charlotte Loveridge based on 28th September performance at the Lyric Hammersmith, Lyric Square, King Street, W6 0QL (Tube: Hammersmith) |

|

London Theatre Tickets Lion King Tickets Billy Elliot Tickets Mary Poppins Tickets Mamma Mia Tickets We Will Rock You Tickets Theatre Tickets |