SITE GUIDE

SEARCH

REVIEWS

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

DC

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

On TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

Writing for Us

A CurtainUp  London Review

London Review

London Review

London ReviewOrestes

|

They call us the matricides

---- Electra |

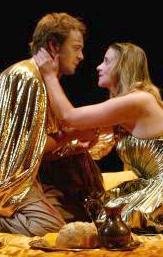

Alex Robertson as Orestes and Mairead McKinley as Electra

(Photo: Robert Day) |

The play opens when Orestes (Alex Robertson) and his sister Electra (Mairead McKinley) have just killed their mother Clytemnestra, in revenge for her murder of their father after he sacrificed one of their daughters. This apparently endless cycle of interfamilial revenge is now halted. Aeschylusí canonical Oresteia had told how the matricide then fled, pursued by the Furies, to Athens to face trial. There, with the establishment of legal democratic justice, Athena appeased the Furies and acquitted Orestes.

This play looks at an abstruse gap in myth: the interval between the matricide and the trial. Introducing contemporary politics and law, Orestesí mythical heroism is judged in fifth-century terms: murder punishable by death. Orestes and his sister strive to persuade their anachronistically world that their deed was just, but failing that, turn to disastrous violence.

Their actions threaten not just other characters, but also to change radically the well-known myth. On the very edge of crisis, Euripides suddenly restores the legendary sequence of events through the appearance of Apollo, who effortlessly resolves the humanly-insolvable dilemma.

Nancy Meckerís production does well at portraying the gritty tension of the original and effectively contains Shared Experienceís customary physical expressiveness until the very last scene. Moreover, Meckler elicits vital yet down to earth performances from the cast of ordinary people with legendary status. Especially good are Alex Robertson as Orestes, haplessly caught up in his fate and Mairead McKinley as Electra, overlooked and overshadowed by the beautiful yet dangerous alpha females of the family: Clytemnestra and Helen (Clara Onyemere).

Niki Turnerís sumptuous design of burnished bronze has a ceiling-high mirror panel, covered in a grid of multiple gold high heels. Within this opulence, Orestes and Electra are visibly unwashed since the murder, forcibly suggesting the guilt within the gold. Lines of blank red manikins people the background of the stage, hinting at the recent slaughter of the Trojan War.

Helen Edmundsonís language is vivid and her dialogue unforced. However, I always feel that it is dubious for a writer to adapt a work which they do not fundamentally believe in. Edmundson freely confesses that her first reaction to Euripidesí Orestes was that of puzzlement, followed by the conclusion that "it is structurally flawed and tonally inconsistent."

Making some radical excisions, Edmundson cuts the chorus, Orestesí comrade Pylades and Apollo. However, I did not think that there was enough substance to replace them. For example, by removing Apollo, Orestes is denied the divine ordinance for his matricide and instead acts out of delusion. In this way, she makes the point that people use religion as an excuse for atrocities. Euripides, on the other hand, used the deus ex machina to expose his cynical view of humanity as flawed and ultimately futile. In spite of democracy, legal justice and reasoned argument, these characters inescapably hurtle towards catastrophe. A godís sudden descent and instantaneous resolution of everything the characters had tried so hard to gain merely highlights by contrast the paltriness of humanity: doomed to tragedy and unable to fight their out of it.

This production is very accomplished, with Nancy Mecklerís expert direction, a convincing cast and superb design. Nevertheless, I felt the losses more keenly than I appreciated the gains in Helen Edmundsonís free adaptation.

|

ORESTES

Written by Helen Edmundson based on Euripides Directed by Nancy Meckler With: Tim Chipping, Jeffery Kissoon, Clara Onyemere, Claire Prempeh, Alex Robertson, Mairead McKinley Design: Niki Turner Movement Designer: Liz Ranken Lighting: Peter Harrison Composer and Sound Design: Peter Salem Running time: One hour 35 minutes with no interval Box Office: 020 7328 1000 Booking to 2nd December 2006 Reviewed by Charlotte Loveridge on 8th November 2006 performance at the Tricycle Theatre, Kilburn High Road, London NW6 (Tube: Kilburn) |