SITE GUIDE

SEARCH

REVIEWS

REVIEW ARCHIVES

ADVERTISING AT CURTAINUP

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

New Jersey

DC

Connecticut

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

Writing for Us

A CurtainUp San Diego Review

The Madness of George III

|

What do you know of my mind?. ..I'm not going out of my mind. My mind is going out of me!—

George III The state of monarchy and the state of lunacy share a frontier.— Dr. Willis |

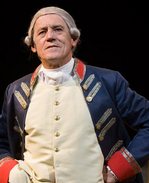

Miles Anderson as King George III

(Photo by Craig Schwartz.) |

When not insane, or pissing off American colonists, he was a sober, steadfast monarch. He remained faithful to his queen during their long and arranged marriage, producing 15 children (Queen Victoria was his granddaughter). Alan Bennett's 1991 play The Madness of George III (which became an award winning film in 1994) chronicles George III's mysterious illness and dramatic mental decline five years after the end of the Revolution (now thought to be the result of porphyria).

George fought tooth and nail to retain both his sanity and his throne. His son, the Prince of Wales, was waiting anxiously for his father to die, and made no attempt to hide his hunger to rule. George's court was ill-equipped to handle his mental instability, no policies having been made to handle a temporary transfer of power. England's government devolved into petty power struggles. The minority party allied itself with the Prince of Wales and plotted to overthrow George, his Prime Minister William Pitt, and their majority party while trying to get the Prince named as Regent. Meanwhile, Queen Charlotte brought in a host of ineffective doctors, laboring under the uninformed medical practices of the time. George was treated with blistering and purges and finally with an early form of behavior modification therapy, but nothing helped. Eventually the disease abated on its own, and George was able to return to the throne.

The play is less about George III specifically as it is about the boundaries between order and chaos, sanity and madness, good government and bad, and about the general human inability to control ourselves. How can we control millions if we can't control ourselves? It's also a thought-provoking companion piece to another of the Old Globe's repertory season, King Lear (my review). Both kings go mad; both lose power, at least temporarily; both are the subject of complicated plots to seize that power.

I foud Lear is a more nuanced production; since the supporting players in George II I are often little more than caricatures in a vintage political cartoon. Miles Anderson as the title character George is the best of an otherwise sadly one-dimensional ensemble. Even with Lear as a bookend, this George III is a victim of its own exaggeration. The subtleties of the various power struggles are often lost. The Prince of Wales (Andrew Dahl) is a fat buffoon, the doctors are bumbling idiots, William Pitt (Jay Whittaker) is apparently incapable of any emotion outside ruthless efficiency.

That being said, this play is not often performed, and it's a fascinating look into a royal life few Americans are familiar with. While I'd recommend Lear over George III , it's worth it to see both for their overlapping views on the downfalls of absolute monarchy--and, by extrapolation, the downfalls of government in general.

I'll be reporting on the third play in this repertory line-up, The Taming of the Shrew early next week.

|

The Madness of George III Written by Alan Bennett Directed by Adrian Noble With Michael Stewart Allen (Fox), Miles Anderson (George III), Shirine Babb (Lady Pembroke), Donald Carrier (Sheridan), Andrew Dahl (Prince of Wales), Grayson DeJesus (Ramsden), Ben Diskant (Greville), Craig Dudley (Dundas), Christian Durso (Braun), Robert Foxworth (Dr. Willis), Kevin Hoffmann (Duke of York), Andrew Hutcheson (Fortnum), Charles Janasz (Thurlow), Joseph Marcell (Sir George Baker), Steven Marzolf (Captain Fitzroy), Jordan McArthur (Papandiek), Brooke Novak (Margaret Nicholson), Ryman Sneed (Maid), Adrian Sparks (Sir Lucas Pepys, Sir Boothby Skrymshir), Emily Swallow (Queen Charlotte), Bruce Turk (Dr. Richard Warren), and Jay Whittaker (William Pitt) with Catherine Gowl, Aubrey Saverino and Bree Welch (Ensemble) Set Design: Ralph Funicello Lighting Design: Alan Burrett Sound Design: Christopher R. Walker Costume Design: Deirdre Clancy Original Music: Shaun Davey Running Time: Two hours and forty minutes with one fifteen-minute intermission The Old Globe; 1363 Old Globe Way, San Diego; 619-23-GLOBE Tickets $29 - $78 Schedule varies June 19 - September 24, 2010 Reviewed by Jenny Sandman based on July 3rd performance |

|

Subscribe to our FREE email updates with a note from editor Elyse Sommer about additions to the website -- with main page hot links to the latest features posted at our numerous locations. To subscribe,

E-mail:  esommer@curtainup.comesommer@curtainup.com esommer@curtainup.comesommer@curtainup.comput SUBSCRIBE CURTAINUP EMAIL UPDATE in the subject line and your full name and email address in the body of the message -- if you can spare a minute, tell us how you came to CurtainUp and from what part of the country. Visit Curtainup's Blog Annex Curtainup at Facebook . . . Curtainup at Twitter REVIEW FEEDBACK Highlight one of the responses below and click "copy" or"CTRL+C"

Paste the highlighted text into the subject line (CTRL+ V): Feel free to add detailed comments in the body of the email. . .also the names and emails of any friends to whom you'd like us to forward a copy of this review. |