SITE GUIDE

SEARCH

REVIEWS

REVIEW ARCHIVES

ADVERTISING AT CURTAINUP

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

New Jersey

DC

Connecticut

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

A CurtainUp Review

The Late Christopher Bean

By Elyse Sommer

|

This mornng I was a peaceful country doctor filled with gentle thoughts of a medical description and I coveted nothing, not even my collections. Look at me now. . . if a patient came in with an appendix now I'd miss it so far I'd put his eye out!.— Dr. Haggetty expressing the effect of discovering that the paintings given to him by his deceased former patient and boarder were not as worthless as he had thought.

|

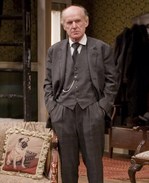

James Murtaugh

(Photo: Stephen Kunken) |

This being the Great Depression Doctor Haggett, the patriarch of this somewhere near Boston house, is hard pressed to maintain all that cozy comfort, let alone pay for the Florida trip on which his socially ambitious wife annually takes their daughters in hopes of their finding well to do husbands. Many of the patients who come to Doctor Haggett's office in another part of the house or seen during house calls are unable to pay for his services. Slow as collections are, Dr. Haggett, unlike today's heavily mortgaged home owners, probably paid up his mortgage long ago so that there's not likely to be an unpleasant surprise like a foreclosure notice.

But there is indeed a surprise in the form of an unexpected financial stimulus for the cash poor Haggetts. It begins with the arrival of a telegram from a New York art expert. He's an admirer of a dead artist (the Christopher Bean of the title) who has been belatedly embraced by the art establishment and who, before his death from tuberculosis and alcoholism, was a patient and non-paying lodger in the Haggett barn.

The events following the arrival of that telegram have all the elements of a screwball comedy-romance. The romance is provided by the younger Haggett daughter Susan and a young house painter with fine arts ambition as well as by Abby, the maid who was Bean's true friend and admirer during his days in the barn. The screwball shenanigans, which build towards the genre's typical chaotic shouting match, revolve around the good Doctor, his avaricious wife Hannah and eldest daughter, Ada being taken in by the scheming New Yorkers.

The various arrivals at the Haggett home offer irresistible opportunities for profiting from the canvases Bean left in the Haggett home. Given that it took New York ten years to recognize Bean's talent, it's quite understandable that the unsophisticated country doctor and his wife did little to treasure and preserve Bean's canvases. The garish floral still life hanging over the family hearth is the untalented Ada's handiwork.

Howard, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his very moving They Knew What They Wanted (later musicalized as The Most Happy Fella), knew not only how to develop his madcap plot with misrepresentations, misunderstandings and missed opportunities, but to give it a satiric edge that has not dulled with time and his characters are more complex than they first appear to be. This is especially true of the Doctor. As characterized by the playwright and wittily portrayed by James Murtaugh, he reveals how even little windfalls have a way of nourishing big time greed in a good man. Murtagh's achievement is to make a man whose fall from honor is not so complete, that you can't help sympathizing with him even when newly nourished greed causes him to behave deplorably.

The play's surface theme that points up the difference between those who view art strictly in terms of its monetary value and those with a more genuine appreciation is the springboard for Howard's larger theme: The moral conflict between greed (exemplified by the Haggetts and their New York visitors, Tallant and Rosen) and the more humane instincts of love and kindness. It is those better instincts that make Abby, the underappreciated maid, the play's true heroine who has you rooting for her when a portrait of her by the late Bean takes on new importance for the various self-serving factions.

Mary Bacon, who was so memorable in the quite different role of Alma Winemiller in TACT's fine revival of Tennessee Williams' Eccentricities of a Nightingale (review), is again superb. She makes the simple Abby sweetly naive, convention bound and yet an open-minded, kind and loving free spirit.

Jenn Thompson, who directed Eccentricities. . . as well as TACT's excellent revival of Alan Ayckbourn's Bedroom Farce (review), elicits good work from the rest of the ensemble who, thanks to costume designer Martha Hally, all look as if they'd stepped out of the pages of a 1930s magazine. But this Murtagh's and Bacon's show.

Ms. Thompson has wisely conflated acts one and two in keeping with modern single intermission formats and kept the madcap elements from going over the top. Since it's rather easy to anticipate the lessons to be learned and the pretenses to be exposed, one can't help wishing that the directer had also managed to trim the play's first half to bring it a bit closer to an hour than an hour and fifteen minutes.

Howard who was also a successful Hollywood screen writer (he was awarded Oscars for his screenplay of Sinclair Lewis's Dodsworth and Margaret Mitchell's Gone With the Wind), based The Late Christopher Bean on a French play, Prenez Garde de la Picture by Rene Fauchois. However, his play was a very loose, distinctly American adaptation. While it had a well-received 224-performance Broadway run (1932-33), it hasn't been seen in New York since; nor has it had any sort of life elsewhere. TACT therefore deserves a big round of applause for giving New York audiences a chance to see this well-acted, handsomely staged production.

|

The Late Christopher Bean by Sidney Howard Based upon Prenez Garde de la Picture by Rene Fauchois Directed by Jenn Thompson Cast: Bob Ari, (Rosen), Mary Bacon (Abby), Hunter Canning (Warren Creamer), Jessiee Datino (Susan Haggett), Cynthia Darlow (Mrs. Haggett), Greg McFadden (Tallant), Kate Middleton (Ada Haggett), James Murtaugh (Dr. Haggett), James Prendergast (Maxwell Davenport) Scenic Design: Charlie Corcoran Costumes: Martha Hally Props: Taline Alexander Lighting: Ben Stanton Sound: Stephen Kunken Music: Mark Berman Stage Manager: Meredith Dixon From 11/01/09; opening 11/11/09; closing 12/05/09. Monday, Wednesday-Friday at 7:30 PM; Saturday at 2 PM & 8 PM; Sunday at 3 PM. Running Time: 2 hours and 20 minutes, includes one 10-minute intermission TACT at The Beckett Theatre 410 West 42nd Street Reviewed by Elyse Sommer based on November 6th press preview |

|

REVIEW FEEDBACK Highlight one of the responses below and click "copy" or"CTRL+C"

Paste the highlighted text into the subject line (CTRL+ V): Feel free to add detailed comments in the body of the email. . .also the names and emails of any friends to whom you'd like us to forward a copy of this review. You can also contact us at Curtainup at Facebook or Curtainup at Twitter |

|

Subscribe to our FREE email updates with a note from editor Elyse Sommer about additions to the website -- with main page hot links to the latest features posted at our numerous locations. To subscribe,

E-mail: esommer@curtainup.comesommer@curtainup.com

put SUBSCRIBE CURTAINUP EMAIL UPDATE in the subject line and your full name and email address in the body of the message -- if you can spare a minute, tell us how you came to CurtainUp and from what part of the country. |