SEARCH

REVIEWS

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

DC

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

On TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

A CurtainUp  London Review

London Review

London Review

London ReviewThe Gunpowder Season

*A New Way to Please You | *Sejanus: His Fall | *Believe What You Will|*Speaking Like Magpies| *Thomas More Editor's Note: An * asterisk will be aded to each title as reviews of the Gunpowder plays are posted.

|

To be taught that difficult lesson, how to learn to die.

---- Lysander |

Members of the Company

(Photo: Stephen Vaughan) |

The first is a modern production of an old Jacobean play with a disturbing theme, A New Way To Please You was originally the subtitle for a play called The Old Law. It is about a Duke who, advised by lawyers, decides that men when they reach 80 years of age and women, 60, should be put to death as they have outlived their usefulness to society. The plays censures the greedy youth and grasping younger wives who are queuing up to despatch their fathers and husbands and shows that, in adversity, loyal sons will hide the aged relative to avoid the law. Callow youths line up to marry rich fifty-nine year old women so that they may inherit shortly.

The whole is played in modern dress so that the three youths who lead the movement are punks, the venues are discos with raucous music. In one scene an eighty year old man Lysander (James Hayes) dresses in a yellow jump suit and in a contest for a young wife beats his youthful challenger, Simonides (Jonjo O'Neill) in both the drinking and dancing contests. It is played as a comedy rather than the tragicomedy referred to in the programme but there are moments which are chilling when faced with the arrogance of punk youth. Cleanthus (Matt Ryan) is the heroic son who defends and hides his father and has many of the play's high moments. Overall there is an energy from the ensemble cast which may please a youthful audience (the 16 to 25 year olds can get a seat for £5). The twenty first century music modern dance at the end parodies the end of play period dance from the practitioners at Shakespeare's Globe. In a world where plastic surgeons coin it as men and women try to look younger than their years, and where rich old men marry young girls, A New Way to Please You has an alarming resonance.

|

A NEW WAY TO PLEASE YOU

Written by Thomas Middleton and Philip Rowley Directed by Sean Holmes With: Jonjo O'Neill, Keith Osborn, Nigel Betts, Matt Ryan, Geoffrey Freshwater, Teresa Banham, Evelyn Duah, Barry Stanton, Peter de Jersey, David Hinton, Jon Foster, Julian Stolzenberg, Keith Osborn, Mark Springer, Fred Ridgeway, Vinette Robinson, Miranda Colchester, James Hayes, Ishia Bennison, Michelle Butterly, Pascal Wyse, Tom Haines, Chris Branch Design: Kandis Cook Lighting: Wayne Dowdeswell Music Sound: Chris Branch and Tom Haines Running time: Two hours thirty minutes with one interval Box Office: 0870 060 6632 Booking to 31st December 2005 Reviewed by Lizzie Loveridge based on 22nd December performance at the Trafalgar Studios One, Whitehall, London SW1 (Rail/Tube: Charing Cross) |

|

You must not see the sun if, in the policy of the state, it is forbidden.

---- Antiochus |

Peter de Jersey as Antiochus and William Houston as Titus Flaminius

(Photo: Manuel Harlan) |

King Antiochus of Lower Asia (played with impassioned energy by Peter de Jersey), was defeated in battle and believed dead. At the start of the play he has spent months or years in hiding, seeking refuge from friendly powers. Now at last he returns to Carthage in beggar's rags to reclaim his kinghood. No-one, friend or foe, for a moment doubts Antiochus's credentials. But he is hounded by Rome, a superpower government determined to discredit him. And when a friendly, accommodating king submits to Roman realpolitik Antiochus is seized, named an impostor and put in shackles for fear that his presence could ignite discontent in the Asian provinces and harm the profitable Mediterranean trade. His chief tormentor is a Roman envoy Titus Flaminius, in William Houston's chilling performance a smiling villain dressed in diplomatic guise, who justifies coercion, torture and cruel punishments on the grounds of necessity of state. Among his victims is Barry Stanton's Berecinthus, a defrocked priest of splendidly Falstaffian proportions with a pithy turn of phrase, who after teasing his Roman captors, eventually finds his great bulk stretching his neck on the scaffold.

Josie Rourke's production is played on the RSC season's apron stage, a timbered expanse flanked by brick enclosures to conceal the source of lighting effects. The stage is otherwise bare and the director uses virtually no design details beyond the costumes: Jacobean for the Romans, timeless togs and skullcaps for the Asians. After years of brutal power politics Flaminius's comeuppance arrives with a brilliant coup de theatre, when Nigel Cooke as Marcellus, a senior Roman politician, orders his staff to bring out his entire collection of swords, to be placed in geometric groupings across the floor until they virtually cover the entire playing area. The idea is that Antiochus, still dubbed a fraud by the increasingly manic Flaminius, can pick out the sword that he long ago gave Marcellus as a gift of friendship, and thus at last prove his true, kingly identity. Only the RSC would have a backstage armoury capable of delivering this closing masterstroke, with its sounds of ringing cold steel, which perhaps could explain why this is the first revival of Massinger's enthralling play since 1631.

|

BELIEVE WHAT YOU WILL

Written by Philip Massinger Directed by Josie Rourke Starring William Houston, Peter de Jersey With: Mark Springer, Nigel Cooke, Ian Drysdale, Jonjo O'Neill, Peter Bramhill, Barry Stanton, Kevin Harvey, Barry Aird, Ewen Cummins, Matt Ryan, Julian Stolzenberg, David Hinton, Tim Treloar, Fred Ridgeway, Evelyn Duah, Michelle Butterly and Teresa Banham Design: Stephen Brimson Lewis Lighting: Wayne Dowdeswell Music: Mick Sands Sound: Andy Franks Running time: Two hours thirty minutes with one interval Box Office: 0870 060 6632 Booking to 11th February 2006 Reviewed by John Thaxter based on the 1st February 2006 at Trafalgar Studios One, Whitehall, London SW1 (Rail/Tube: Charing Cross) |

|

My lord, for to deny my sovereign's bounty/

Were to drop precious stones into the heaps /Whence they first came; To urge my imperfections in excuse, /Were all as stale as custom: no, my lord, /My service is my king's; good reason why,/ Since life or death hangs on our sovereign's eye.

---- Thomas More |

Nigel Cooke as Sir Thomas More

(Photo: Hugo Glendinning) |

The play which opens with More's enlightened handling of riots against foreign nationals has a middle interval of More in high office entertaining dignitaries to a play within a play, The Marriage of Wit and Wisdom. But the final thrust of the play concerns More's arrest, imprisonment and journey to the scaffold. It is a little like speed history as the events of 18 years are condensed.

The riot scenes are very well staged and played and, with the play in modern dress, their xenophobic origins strike a contemporary note. The play has wonderful music and is strong on atmosphere. The final scenes too work well as More resists the pressure to conform and pays with his life and the financial security of his family. Nigel Cooke holds the stage as More and convinces eloquently and his highpoint is the quelling of the riot, his speech pleading for common decency towards others:

"Imagine that you see the wretched strangers,

Their babies at their backs, and their poor luggage,

Plodding to the ports and coasts for transportation,

And that you sit as kings in your desires . . . "

The main interest for many of the audience is in spotting those lines which Shakespeare might have had a hand in and the Royal Shakespeare Company must be congratulated for staging this rare piece so successfully. For another take on Sir Thomas More see the revival of Robert Bolt's 1966 play at the Haymarket.

|

THOMAS MORE

Written by Anthony Munday, William Shakespeare and others Directed by Robert Delamere Starring Nigel Cooke With: Keith Osborn, Nigel Betts, Geoffrey Freshwater, Teresa Banham, Evelyn Duah, David Hinton, Jon Foster, Julian Stolzenberg, Mark Springer, Fred Ridgeway, Vinette Robinson, Miranda Colchester, James Hayes, Michelle Butterly, Kevin Harvey, Barry Aird, Ian Drysdale, Ewen Cummins, Peter Bramhill, Tim Treloar, Michael Jenn Design: Simon Higlett Season Stage designed by Robert Jones Lighting: Wayne Dowdeswell Music: Ilona Sekacz Sound: Mike Compton Running time: Two hours thirty minutes with one interval Box Office: 0870 060 6632 Booking to 14th January 2006 Reviewed by Lizzie Loveridge based on 5th January 2006 performance at the Trafalgar Studios One, Whitehall, London SW1 (Rail/Tube: Charing Cross) |

|

I will commit a race of wicked acts…

Though heaven drop sulphur, and hell belch out fire,

…Tell proud Jove,

Between his power and thine there is no odds:

'Twas only fear first in the world made gods!

---- Sejanus |

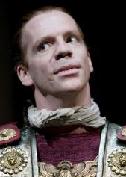

William Houston as Sejanus

(Photo: Stewart Hemley) |

The play opens just after the death of Germanicus, the darling of Rome and the bane of the unpopular Emperor Tiberius (Barry Stanton). Amid the political upheaval, Tiberius relies increasingly on the lowly-born but voraciously and deviously ambitious Sejanus (William Houston), the prefect of the praetorian guard. Sejanus manipulates Tiberius' anxiety over Germanicus' surviving family so that they are effectively doomed. He also insidiously attacks Tiberius' son Drusus (Matt Ryan), turning his own household against him by seducing his wife Livia (Miranda Colchester) and servant boy Lygdus (Peter Bramhill). However, Sejanus' plan to become Tiberius' heir triggers the mistrustful emperor's suspicions. Tiberius creates a substitute for Sejanus in the figure of the chillingly impassive Macro (Peter De Jersey). It is not long before Sejanus becomes a victim of the ruthless world he had personified. Senators, meanwhile, are split between the honourable and therefore short-lived, or the capriciously sycophantic self-seekers who thrive.

William Houston's central performance as the Machiavellian Sejanus is what really makes this production so powerful. Breathtakingly compelling. His villain is the most charismatic and intelligent character onstage and inspires fascination as much as terror. His reptilian gluttony for power suggests how singularly easy it is for the unscrupulous to destroy the honest. As he executes his extensive, intricate and intrepid schemes with ease, Houston plays an exultant Sejanus who positively flourishes in the midst of deception and intrigue. Similar to Iago, his monologues draw the audience into an uneasy complicity, while his piercing, all-inclusive eye contact makes him seem as if he is scrutinizing even the auditorium for threats or opportunities.

The rest of the characters have a vivid individuality. Barry Stanton's Emperor Tiberius is circumspect, decadent and capable of any measures to keep his reviled reign secure. Miranda Colchester's unfaithful Livia is vain and frivolous amid murderous plans. The honest, disgruntled Romans like Geoffrey Freshwater's Silius or Nigel Cooke's Arruntius combine their stifled moral outrage with powerlessness. I also liked Jon Foster's portrayal of Caligula, clearly establishing the future emperor's monstrosity as Tiberius' corrupting power.

At two hours and fifty minutes this play is not exactly lightweight. Instead, it is a meaty and satisfying portrayal of a society in a state of irreversible decay, with sinister power games, unprincipled ambition and violent deeds. The only drawback is the shortness of Sejanus: His Fall's run!

|

SEJANUS

Written by Ben Jonson Directed by Gregory Doran Starring William Houston With: Nigel Cooke, Barry Stanton, Matt Ryan, Miranda Colchester, Nigel Betts, Peter Bramhill, Ishia Bennison, Jonjo O'Neill, Jon Foster, Vinette Robinson, Geoffrey Freshwater, James Hayes, Keith Osborn, Peter De Jersey, Barry Aird, Ewen Cummins, Kevin Harvey, Ian Drysdale, Michael Jenn, Tim Treloar Design: Robert Jones Lighting: Wayne Dowdeswell Music: Paul Englishby Sound: Martin Slavin Running time: Two hours fifty minutes with one interval Box Office: 0870 060 6632 Booking to 28th January 2006 Reviewed by Charlotte Loveridge based on 18th January 2006 performance at the Trafalgar Studios One, Whitehall, London SW1 (Rail/Tube: Charing Cross) |

|

You know the ending. The King is not killed and the plotters are captured

---- The Equivocator |

Peter Bramhill as Dog

(Photo: Hugo Glendinning) |

Instead of a straightforward historical narrative, McGuinness' exploration of the seventeenth century plot is imaginative and has elements of the surreal. For example, there is a central figure of The Equivocator (Kevin Harvey). Dressed as a satyr, he has cloven hooves, horns and pointed ears. He is a tempter and a taunter, enjoys omniscience and can appear to whoever he wishes.

King James I (William Houston) is an enigmatic figure, haunted by his Catholic mother's persecution at Protestant hands, but not merciful towards the Catholic traitors. He might enjoy mortal sovereignty but none of his subjects can save him from the fear of his inevitable death. The excellent William Houston brings out the full ambiguity of the part without sacrificing the interest he inspires.

There are a host of other vivid characters: James' unloved Queen (Michelle Butterly), the dashing, intense conspirator Catesby (Jonjo O'Neill) and his friend who mirrors his every move (Matt Ryan). There is also the Spymaster Robert Cecil, who wears period dress made completely out of black leather (Nigel Cooke), Henry Garnet, the Catholic priest in hiding who unwillingly hears of the murderous plan (Fred Ridgeway), and May the young, innocent servant who is literally obliterated by the momentous events (Vinette Robinson).

With so large and varied an ensemble, the play's cohesion might seem a little lacking, but the character threads are brought together for a satisfying ending. As usual, Frank McGuinness' writing is exuberant and adds great pace to a deeply-textured, weighty subject. He does not pursue parallels with modern, religiously-motivated terrorism, but the play is rather a more timeless portrayal of humanity. Moreover, there are some fantastic, almost witty, pyrotechnic effects. This production is a superior, if somewhat bizarre, conclusion to the RSC's successful Gunpowder season.

|

SPEAKING LIKE MAGPIES

Written by Frank McGuinness Directed by Rupert Goold Starring William Houston With: Nigel Cooke, Kevin Harvey, Teresa Banham, Vinette Robinson, Miranda Colchester, Jon Foster, Keith Osborn, Julian Stolzenberg, Peter Bramhill, Fred Ridgeway, Ishia Bennison, Barry Aird Design: Matthew Wright Lighting: Wayne Dowdeswell Music and Sound Score: Adam Cork Music Director: Michael Tubbs Running time: Two hours twenty-five minutes with one interval Box Office: 0870 060 6632 Booking to 25th February 2006 Reviewed by Charlotte Loveridge based on 15th February 2006 performance at the Trafalgar Studios One, Whitehall, London SW1 (Rail/Tube: Charing Cross) |