SEARCH

REVIEWS

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

LA/San Diego

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

On TKTS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

NYC Weather

A CurtainUp DC  Feature

Feature

Feature

FeatureA Summer of Greek Theatre

by Rich See

This spring and summer a variety of adaptations on Greek classics are

arriving to area stages. This ongoing review will be looking at each

one and -- hopefully -- make a few correlating observations on the

interrelatedness of each.

|

Click on Show Title or Scroll Down Page to Browse

The Myth Project: Greek|Heracles|Electra | Thersites | I, Cyclops | Medea | Ion | Gladiator | The Persians|

Reviews

The Myth Project: Greek

As we wrap up our spring and summer of Greek theatre, a new company has emerged that is dedicating itself to exploring the concept of myth as it relates to our own current global culture. The Myth Project is seeking to explore not only the Greek and Roman tales, but also African and Oriental mythology, as well as urban myths and fairy tales. Their ultimate goal is to "find the collective truths in the ancient stories." To initiate their endeavor, they began with the Greek adventures.

A series of separate one acts, The Myth Project: Greek is more a grouping of works in progress. Its three writers have contributed four stories -- each based upon elements of Greek mythology -- and each an examination of how those same archetypal images work through our American culture today. And this offers the viewer a wonderful sense of relevance of how these energies (humor, tragedy, love, etc.) have manifested through humanity in much the same ways since the dawn of time.

In Karen Currie's "Cessa and the Copier" a spoiled, gossiping young woman not only attacks the office Xerox, but also attempts to nose her way into her friend's romance. Gina the friend is involved with Cessa's uncle and Cessa is instigating simply for the sole reason of entertaining herself at the expense of others.

It's a comedy with great flow that is assisted by the physical humor of Dan VanHoozer (the copier) and Ann DeMichele (Cessa). However it shows more serious implications if we expand the piece's view from simple office politics to broader societal aspects. The image of Cessa could easily become the image of a 24 hour cable news channel. And her gossiping about an office affair just as easily converts to "hard news coverage" of salacious stories designed to entertain the country and generate ratings-oriented advertising dollars for corporate interests. When Cessa gets her comeupance, one has to wonder what awaits the country that gleefully watches a celebrity pedophilia case with less interest in the plight of the children involved than in enjoying the freak show being presented.

"The Open Box" by Jack Robertson is a timely play upon Pandora's Box. Gay rights activists -- touchingly played by Jeff Davis and Paul McLane -- blow up the U.S. Navy Memorial in downtown Washington, DC. The act is in an attempt to bring attention to encroaching second class citizenship being thrust upon the United States' GLBT community. (If only these queer "terrorists" had a straight celebrity pedophile freak show to juxtaposition their cause against, they wouldn't have to resort to bombs!) The piece is at once funny and tragic as it looks at the exasperation average people feel when trying to simply live their lives in the face of continuing cultural adversity.

While slightly confusing, Dan VanHoozer's "The Song of Procne" calls forth a Greek epic poem. The story of a hummingbird (or is she a woman?) seeking revenge upon her "glorious warrior" husband is poetic in language and timing. Jennifer Cooper's hummingbird has sought to avenge her husband's arbitrary rape and mutilation of her sister by -- in the best tradition of the Greeks -- killing, roasting and serving her small son to his father. Just like Medea, her anguish has eclipsed her reasoning, and after her gruesome act, she has fled her home.

Unlike Medea, Procne has become caught in a tree. The tree is a metaphor for grief and misery, while its falling leaves represent emotional release. Alas, autumn (that time of letting go) is a long way off since the tree is in full, green, leafy bloom. Thus with no relief, Procne's grief dooms her to almost certain death from starvation (lack of redemption from her guilt) or being eaten by a mouse (her own inner terrors). The irony being that her last meal was her own child (her offering to humanity). Taking this same imagery, one can easily look about and find people today who destroy their own self-nurturing creative ventures out of anger, bitterness and spite towards others. And like Procne they become stuck in their own inner pain.

Accompanied by Ann DeMichele's haunting solo, Jennifer Cooper navigates the emotional piece well, as she swings from rhapsodic to tearful to practical and muses "I served him with a ginger peach chutney . . A better cook would have used all of her son."

Probably the mot polished and visually stunning of the pieces is Jack Robertson's "Creation and the Ages of Man," which is a dance/theatre performance that takes us through the Greek's five stages of humanity. Using whimsical balloons, the dancers create the Ages of Gold, Silver, Bronze, and that of Hero-Men & Demi-Gods. Soon the three actors share the story of Prometheus and his gift of the Age of Fire, which is where we find ourselves today.

While still obviously rough in spots, The Myth Project: Greek is a good example of what is percolating within DC's smaller theatre community. There is a vibrancy and relevance here that allows new works to be incubated and developed; something most cities of a similar size do not provide. For their next foray, the company may want to include more extensive liner notes on the pieces, as well as the correlating myths from which the works are derived.

Not here for very long, the short run ends on Wednesday, August 17th. But to provide a look at how we are still, in contemporary times, adding to our mythological canon, I wanted to add this review to our ongoing examination. Like the adaptations of other Greek stories we have seen this year, these one acts offer a wonderful opportunity to examine our own lives and world in ways that are not so inherently threatening to our psyches. As an actress recently said to me "I am in a healing profession." and these stories help us see patterns that still play out, not only on our cultural landscapes, but in our inner lives as well.

As The Myth Project so eloquently states in its program "The origin of the mythological history is the origin of theatre...tribesmen telling the great tales to teach lessons about life." Healing begins when we can see where we may need to apply the salve.

|

The Myth Project: Greek by Karen Currie, Jack Robertson and Dan VanHoozer directed by H. Lee Gable, Dan VanHoozer and Genevieve Williams with Ann DeMichele, Dan VanHoozer, Jennifer Cooper, Joe Angel Babb, Jeff Davis, Kimberly Braswell and Paul McLane Running Time: 1 hour 15 minutes with no intermission A production of The Myth Project at Clark Street Playhouse, 601 South Clark Street, Crystal City, VA Telephone: 202-397-8255 SUN - WED @ 8; $15 Opening 08/3/05, closing 08/17/05 Reviewed by Rich See based on 08/10/05 performance |

Heracles

|

God can bear to know what we can not --Professor Hoadley |

|

John Tweel (Herakles), MaryAnne Mosher (Megara), Margaret

Contreras (Xenoclea) (Photo: Stan Barouh)

|

The first half of the piece takes us to a Greek hotel room and the failing marriage of the arrogant and recent Nobel prize winner Professor Hoadley and his unhappy wife as they battle out their grievances in a veiled discussion of the greatness of the Greek mythological heroes. The second act takes us to the temple of Delphi where Mrs. Hoadley, her daughter and nanny undertake to find out what happened to Herakles once his famous labors were completed.

Mr. MacLeish provides us with an interesting discussion, as his flowing writing and poetic language offer us a look into our own psyches. He asks us to examine ourselves as we overcome our own labors and look at "What happens when the trying is over?" And " When does the journey of life become simply enough?" It's an interesting point as expressed by Professor Hoadley's wife when she asks "What would we have to love? To bare? To care for, without the suffering?" It's a simple question, but one that throws the professor into a rage as he deals with arriving at the celebrated heroic completion of his own work and grapples with how to simply go home and become a regular human being again.

Director Rip Claassen has pulled together a wonderful cast which provides interesting layers of humor and drama as it explores what happens when the heroics are over and the hero returns home. Michael Null's sound design incorporates pan flute music by Brad White, which adds to the atmospheric ambiance of the George Washington Masonic National Memorial's amphitheater. Franklin Coleman's lighting design provides nice moments and utilizes the space well. Trena Weiss-Null's costumes go well with the characters and her set creates an appropriate time period of hotel comfort and ancient Greek ruins. However, the set change between acts is something that needs to be worked on since it adds an unnecessary lengthening to the performance. Although, I'm sure this is something that has been taken care of at this point in the run.

Margaret Contreras shines in both the roles of the fawning hotel manager and as the prophetic Xenoclea. She brings humor to the first and realistic possession to the second. As Professor Hoadley, Bruce Alan Rauscher adds a surprising level of uncontrolled anger to the role of the academic who is confined to a wheelchair. When you see him in Act Two as the Guide, his carefree attitude makes him almost unrecognizable. The goatee he wears as the professor though, would be better suited for the guide.

As Mrs. Hoadley, Deborah Rinn Critzer creates a liberating force as she moves from embittered wife to emancipated woman. Her delivery of MacLeish's lines shows an understanding of poetry and its rhythms.

In the roles of Herakles and his wife Megara, John Tweel and MaryAnne Mosher, offer us a look into the dysfunctional household of the Age of Heroes. Ms. Mosher's touching Megara is a woman who has literally kept the home fire burning for twelve years, only to find it all for naught. Having sent her sons out to greet their father, she discovers that in the tragic end she is still alone as her husband chooses yet another quest over life with her. Meanwhile, Mr. Tweel gives us a Grecian hero who is more man than brawn, and who one can envision having just come from a game of hero marauding with the boys. His Herakles is extremely likeable and he takes you beyond the lion skin he is wearing to enter into the mind of a man who is trying to understand the unknowingly spiritual aspect of the quest he has been on all these many years.

The rest of the cast is filled out quite nicely by: Caroline Gotschall, Kate Hundley, James Senavitis and James Thomas King, Jr.

Again, it's recommended that you sit in the center area of the amphitheater since the acoustics can sometimes be sketchy. And while Mr. MacLeish's Herakles time line may not be exactly as the ancient Greeks wrote it, the story is an interesting melding of modern and ancient mythological themes. Herakles shows us that -- like the archetypal myths of old -- if we choose to battle our own inner demons, we take what Joseph Campbell called, The Hero's Journey. Happy voyaging!

|

Herakles by Archibald MacLeish directed by Rip Claassen with Margaret Contreras, Bruce Alan Rauscher, Deborah Rinn Critzer, Caroline Gotschall, Kate Hundley, James Senavitis, James Thomas King Jr., MaryAnne Mosher, John Tweel Set Design: Trena Weiss-Null Sound Design: Michael Null Lighting Design: Franklin C. Coleman Costume Design: Trena Weiss-Null Properties: Theoni Panagopoulos Running Time: 2 hours with one intermission A production of Natural Theatricals http:// www.naturaltheatricals.com The Amphitheater of the George Washington Masonic National Memorial, 101 Callahan Drive, Alexandria, VA Telephone: 703-739-5895 WED - SAT @ 8, SUN @ 2; $20 Opening 08/05/05, closing 08/28/05 Reviewed by Rich See based on 08/05/05 performance |

|

My life is like a river, it floods with grief... ---Electra |

Reviews

Electra

|

My life is like a river, it floods with grief... ---Electra |

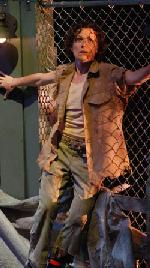

J. Mendenhall

(Photo: Christopher O. Banks) |

Written by Sophocles sometime between 420 and 413 A.D. the Electra myth shares the story of the House of Atreus. Once a mighty man, Atreus was killed by Aegisthus with the help of Atreus' wife Clytemnestra. While Clytemnestra insists her participation in the plot was to exact revenge upon Atreus for sacrificing one of their daughters to the gods, she has since married Aegisthus and would like to see her son Orestes dead. During the tragic evening when Aegisthus and his men attacked the home of Atreus, Electra smuggled Orestes (who's death was also plotted) out of the country with a trusted servant. It is for this crime that Electra is imprisoned in her own home and enslaved as a servant by her own mother. Needless to say the mother-daughter relationship in this family is not very amiable.

Sophocles' story enters many years later when the grown Orestes has decided to return and reclaim his rightful place as the head of the house and to exact revenge upon all who participated in his father's murder. Electra has spent the intervening years crying and lamenting her miserable fate, refusing to be overcome by the powerful force against her. Her sister Chrysothemis meanwhile has played the game and although she reviles her stepfather and mother, sees little help available to the two women. Not wishing to become an abused outcast like Electra, she holds her grief inside in order to face the realty of the situation, which contrasts with Electra, who is at times insane with grief. And so the sisters, unable to handle their vastly different ways of coping, part ways. Unbeknownst to them, Orestes is lurking in the shadows and devising a plot to enter the house and exact his revenge upon his mother and her husband.

Frank McGuinness' adaptation sets the entire staging in a small prison-like compound. The rubbish of the murdered owner's belongings simply decaying outside while the criminals live in comfort inside. His Electra is a combative figure roiling in her misery, hoping for some relief from the outside world, yet always unable to keep her constantly shifting emotions to herself, thus ensuring abuse by her own family. Now a grown woman she remains emotionally a child due to the tragedy that surrounds her and the grief that she so readily embraces and refuses to let pass.

Director Michael Russotto has obviously pushed his cast -- and especially his lead -- to maintain a sense of emotional urgency and tautness. Even if you already know the story, this production keeps you on the edge of your seat. The production points out the timelessness of the tale by adding a modern sense of organized crime and competing crime families. (The House of Atreus is not without its skeletons.) There is a heavy urban industrial sense about the show that shows up in the set design, costumes and Matt Rowe's evocative sound design.

James Kronzer's wonderful set places the action in what looks like a junkyard. Chain link fence surrounds the stage and trash and decaying furniture are heaped about. An automatic detection system keeps Electra imprisoned as a gate closes off the property anytime she nears the perimeter. In stark contrast to this despairing site is the Greek temple-like home, which is painted in Easter colors of pastel yellows, purples and reds. It looks almost cartoonish against the urban grittiness about it, as if mocking the tragedy that has befallen it.

Debra Kim Sivigny's costumes are similarly composed. Electra is outfitted in battle fatigues. Orestes and his men in dark leather jackets and muted modern clothes while Aegisthus is dressed in a polished suit and seemingly drives a large sedan. Meanwhile Clytemnestra and Chrysothemis, wearing sunglasses and pastel colors, each look like they just arrived from a shopping excursion at an upscale mall. The all-female chorus who speak in unison or as alternating voices of the same thought are dressed individually as servants and a family friend.

Jennifer Mendenhall is a dynamic Electra. She has obviously thrown herself into this role and it shows in every word and movement she makes. Ted Feldman makes a quietly powerful Orestes who gives the impression that a ruling crime don has come back to claim his own. Rana Kay is compelling as a misunderstood Chrysothemis showing the tempered sanity that Electra is seemingly lacking.

Maura McGinn and Brian Hemmingsen as Clytemnestra and Aegisthus are engagingly unrepentant and unsympathetic characters. Ms. McGinn looks the part of a Potomac housewife who is more concerned about her physical luxuries than the prison-like environment in which she resides. Mr. Hemmingsen meanders on stage with such attitude that you wish his character's part had been larger.

Among the rest of the cast, Keith N. Johnson and Dallas Darttanian Miller are Orestes' companions who have returned with him from abroad, while Kate Debelack, Debra Mims, and Doris Thomas make up the three person Greek chorus.

I have only one suggestion for this superb production --- the urn that houses Orestes' ashes -- someone needs to take off the "Made in..." (China maybe?) label on the bottom. Although, I'm probably the only person who has noticed it...

|

Electra by Sophocles Adapted by Frank McGuinness Directed by Michael Russotto with Keith N. Johnson, Dallas Darttanian Miller, Ted Feldman, Jennifer Mendenhall, Rana Kay, Maura McGinn, Brian Hemmingsen, Kate Debelack, Debra Mims, Doris Thomas Set Design: James Kronzer Costume Design: Debra Kim Sivigny Lighting Design: Lisa L. Ogonowski Sound Design: Matt Rowe Running Time: 1 hour and 20 minutes with no intermission MetroStage, 1201 North Royal Street, Alexandria Telephone: 800-494-8497 or 703-548-9044 THUR - SAT @8, SUN @2 & 7; $32 - $38 Opening 04/21/05, closing 05/29/05 Reviewed by Rich See based on 04/28/05 performance |

Thersites

|

Zeus...he came, he saw, he humped. ---Thersites |

C. Jahncke

(Photo: Ian C. Armstrong) |

Mr. McNamara has taken three classic stories and rewritten them with a modern sensibility. Thersites is the first of the three parts, upcoming are I, Cyclops and Gladiator. The first two will run in repertory through June and then Gladiator and Scena's upcoming The Persians will run through July and into August. It's all part of Washington's unofficial spring and summer of Greek theatre.

Director Gabriele Jakobi has taken the story and, along with Mr. Jahncke, created a raw, disturbing, and at times funny production. Set 3000 years ago outside the walls of Troy, we are reminded how the terrain of the land must have looked in a time of little medical assistance and modern conveniences. A war-torn wasteland of disabled and diseased people occupying a barren terrain of blood and dirt. It's not a pretty picture and to be honest, Thersites is at times difficult to watch for its shear unfiltered, cerebral graphicness.

Melanie Clark's costume combines modern army garb with a Greek tunic that mixes well with Michael C. Stepowany's dark set. Marianne Meadows lighting is alternately harsh and then dim, while Gabriele Jakobi and David Crandall's sound design incorporates bomb blasts, Elvis songs, and romantic lilts to bring key points home.

It's Mr. Jahncke's performance though that attracts and maintains your attention. Whether he is spitting vitriol or playing the harmonica it is hard to take your eyes off of him, although with his bandaged nose he is somewhat repellent. His ability to quickly move between comedic moments, dramatic monologues and physical humor is most highlighted when he sits down to eat a piece of meat and then realizes it may be a bit of lamb. The resultant pathos is simultaneously funny and heartrending.

Bringing out the subtle, deadpan humor of the play, he announces he is no angel and readily admits that he did "a little sheep fucking" -- at eight years old. This was just prior to his recruitment by the bullying and blind Mr. Sanger -- kind of the army recruiter of his day, you might say. Suffice it to say that Thersites has no use for the Greek heroes of his day and has an entirely different take on their natures and motivations. And when he answers the question "For which of you men can live without honor?" it's no surprise that he states without irony "...all my metaphorical and physical hands went up."

At 45 minutes, the production is just the right amount of time. At the end of it, you begin to tire of the character's inner victim -- his bitterness emerges from the fact that he placed his personal power into the hands of Sanger and then discovered that Sanger led him astray. Although Mr. Sanger simply seems to have capitalized on Thersites lust for violence and desire for adventure and fame.

Mr. McNamara's tendency to run through lists of repetitive words -- i.e. murder, slaughter, butcher, carnage, etc -- in the same monologue can be a bit detracting. And the character's obsession with the homosexual nature of the Greeks is a bit disheartening for gay audiences, since it emerges as an odd example of ancient gay bashing. It seems to be there more to titillate a straight audience than for any artistic merit and soon becomes tiresome.

On a whole though, if you are in the mood for an in-your-face piece of humorous drama, then Thersites is a good ticket.

|

Thersites

by Robert McNamaraDirected by Gabriele Jakobi with Carter Jahncke Set Design: Michael C. Stepowany Lighting Design: Marianne Meadows Sound Design: Gabriele Jakobi and David Crandall Costume Design: Melanie Clark Running Time: 45 minutes with no intermission A production of Scena Theatre Warehouse Theater, 1021 Seventh Street, NW, Washington DC Telephone: 703-684-7990 WED - SUN -- in repertory, call for schedule; $25 Opening 05/23/05, closing 07/17/05 Reviewed by Rich See based on 06/04/05 performance |

I, Cyclops

|

How should I cook these little men? ---Polyphemus the cyclops |

B. Hemmingsen

(Photo: Ian C. Armstrong) |

As both writer and director, Mr. McNamara has an interesting opportunity to see his full creative vision to stage. And the entire play works well both on a dramatic and comedic level. There are about 12 minutes that could be edited out -- lists of verbs or adjectives, too many gay bashing-like expletives, and an odd dream sequence that prolongs the ending and during which some of the audience, including myself, got lost and couldn't figure out where it was going. But other than that -- and those are truly small issues -- the production is a tiny little gem of dark humor with a certain comedic elegance.

Employing Brian Hemmingsen as Polyphemus, the director has found an actor who projects himself into larger than life proportions while maintaining a tongue in cheek roguish quality. It's endearing and also quite funny as you realize this monstrous giant is a gourmand who happens to enjoy human flesh. Since he isn't a man, he doesn't really see anything wrong with consuming a few dozen soldiers. And aside from the errant sailor that he finds and consumes, Polyphemus is for the most part a vegetarian who rhapsodizes over wine, cheese and olives.

Michael C. Stepowany's set design utilizes the staging for Thersites with which I, Cyclops is running in repertory. The sandbags have been hauled away and a simple table and chair have been placed within the center of the stage to create the cyclops' cave. Additionally, a TV -- representing the cyclops' all seeing eye -- has been hung in a corner of the stage and remains on static fuzz epitomizing Polyphemus' blindness. When the audience arrives in the theatre, Mr. Hemmingsen is lying on the floor, much like Mr. Jahncke in Thersites. A harmonica again makes an appearance, this time to accompany the blues.

Marianne Meadows' lighting is a series of rising and falling white lights, while Alessandra D'Ovidio's costume for Mr. Hemmingsen is comprised of a white suit, black shirt and dark impenetrable sunglasses. A simple bandage covers the center of Mr. Hemmingsen's forehead. And as in Thersites, David Crandall's sound makes use of popular culture songs.

The joy in the play though is in watching Mr. Hemmingsen prance and lumber about the stage. When he reenacts his ravishing of Odysseus' troops, it's incredibly funny. And then his understated "not bad" accompanied by a belch adds more laughter to the proceedings. Just as quickly he embarks into an alluring centerfold pose upon the table and then falls into a despondent melancholy at his fate, which is one of impending death for both he and his beloved sheep if he doesn't come out of his cave and face his present life head on. Thus when he says "I am eyeless on my island...I can no longer get up, no longer speak...will night never fall..." there is a great deal of pity for this once proud creature that instilled terror in the hearts of men but who was much beloved by Snow Pea, Sweet Meat and the rest of his ovine flock.

|

I, Cyclops

Written and Directed by Robert McNamarawith Brian Hemmingsen Set Design: Michael C. Stepowany Lighting Design: Marianne Meadows Sound Design: David Crandall Costume Design: Alessandra D'Ovidio Running Time: 1 hour 15 minutes with no intermission A production of Scena Theatre Warehouse Theater, 1021 Seventh Street, NW Telephone: 703-684-7990 WED - SUN -- in repertory, call for schedule; $25 Opening 06/04/05, closing 07/17/05 Reviewed by Rich See based on 06/06/05 performance |

Medea

|

Try teaching new ideas to stupid people. ---Medea |

The high-energy is assisted by Giorgos Tsappas' red circle stage, which contains a sandbox in its center. It seems to be symbolically stating that the child mentality of revenge is the crux of this story and is the ultimate undoing of all concerned.

Ayun Fedorcha's blood red lighting adds to the whole effect of murder and death. While Melanie Clark's simple, muted color costume styles use sashes to denote royalty and keep everyone barefoot.

In the title role, Delia Taylor alternates between wittily comic and disturbingly bent on destruction. Alternately tortured and torturing, she offers a highly emotional performance that uncomfortably pulls you into her skewed world view. Like the Uni-Bomber she seeks revenge, however in lieu of the postal service she's using her children to carry out her misdeeds.

The role of Jason is filled by Jenifer Deal, who does a wonderful job as the once hero, now family man. Christopher Henley creepily fills King Creon's shoes as the monarch who makes two fatal mistakes. The first in getting Jason to marry his daughter, the second in allowing Medea to stay in Corinth for twenty-four hours after ordering her banishment.

Alexander Strain is our narrator, a slave who offers a birds-eye view of the proceedings. Richard Mancini is King Aegeus, who promises Medea refuge without knowing her ultimate motives. And Kathleen Akerley and Debbie Minter Jackson are the Greek Chorus who act as Medea's conscience and advisors.

WSC states that this production is an attempt to bring a little insight into the mind of Euripides' distraught wife and mother by moving beyond basic revenge and insanity themes. I'm not sure that they have accomplished that goal. Much like the stated objective of casting a woman in the role of Jason was to explore the sexual politics of the play. Again, that didn't really seem to occur. However, WSC has provided a wonderful example of an individual so invested in her own pain and misery -- her own victimhood -- that she becomes a pariah to everyone around her.

In many ways, Medea is the precursor to Hedda Gabler and Oscar Wilde's Mrs. Erlynne (Lady Windemere's Fan currently playing at the Shakespeare Theatre--review). As the original anti-mother she is a woman who is quite willing to sacrifice her motherly affections for her own purposeful ends. Unconcerned with winning "Parent of the Year," she is more obsessed with her own vindication than her children's ultimate survival. Indeed, she views their deaths as necessary for completing her own plan of ultimate destruction in bringing down the golden (fleece) House of Jason.

Unlike Ibsen's Hedda Gabler who decides the best thing is to blow her own brains out or Wilde's Mrs. Erlynne who honestly surmises that motherhood is not her cup of team, Euripides' Medea cloaks her actions in lofty language that ultimately rings hollow. So willing to immerse herself in her own pain -- and stay there -- she loses her humanity as she appeals to the gods to show her mercy. A mercy, that she herself is unwilling to show anyone else.

So is she insane or a calculating, selfish woman willing to destroy her own offspring for revenge? Is she a confused Krystal Carrington or a scheming, back stabbing Alexis Carrington Colby? And if she had a really good lawyer in today's world, would she get off the murder rap? After all she is a celebrity of her time. And we all know how celebrities' experiences within the judicial system are not quite the same as the average person's. . .

One thing is certain -- many adults use their children for selfish purposes every day of their charge's young lives. How many divorced parents use their children as pawns of revenge to get back at their ex-spouse? How many parents push their children into performing when all the kid really wants is to go outside and play? Medea...the original Mommie Dearest.

|

MEDEA by Euripides Translated by Alistair Elliot Adapted and directed by Jose Carrasquillo and Paul MacWhorter with Kathleen Akerley, Jenifer Deal, Christopher Henley, Debbie Minter Jackson, Richard Mancini, Alexander Strain, Delia Taylor Set Designer: Giorgos Tsappas Lighting Designer: Ayun Fedorcha Costume Designer: Melanie Clark Puppet Designer: Marie Schneggenburger Running Time: 1 hour and 20 minutes with no intermission A production of Washington Shakespeare Company at WSC Clark Street Playhouse, 601 South Clark Street, Crystal City, VA Telephone: 703-418-4808 THU - SAT @8, SAT - SUN @2; $22-$30 Opening 06/02/05, closing 07/03/05 Reviewed by Rich See based on 06/19/05 performance |

Ion

|

You can do what can be done and kill your husband, then kill the child. ---Old Tutor to Kreousa |

Kind of a precursor to Shakespeare's comedy-dramas, which also incorporate mystic happenings, family tragedy, near death events and then a deus ex machina quick wrap up; Euripides' tale follows the divine reuniting of Kreousa, Queen of Athens, with her son Ion. Kreousa has come to the Delphi oracle to discover why she and her husband Xouthos continue to remain childless. When they arrive they meet a nameless, orphaned young man who cares for the grounds of the temple.

As the story unfolds, we discover that Kreousa was, as a young girl, raped by the sun god Apollo. Conceiving his child, she gave birth to it in secret and then left it at the mouth of the cave where he raped her. Her thought was that, since she could not care for the boy, the god could. Apollo, seeing all from his daily ride across the sky, sent his half-brother Hermes to rescue the infant and take it to his temple in Delphi. There the priestess of the temple took the child in and brought him up, employing him to care for the temple's grounds.

Now almost twenty years later, Apollo is bringing the story to completion as he works to reunite mother and son and create a family of rulers in his name. However, the people involved, not understanding what is going on, decide to take matters into their own hands and this causes a few problems.

Euripides adds some interesting aspects to his tale. His Greek chorus -- Queen Kreousa's servants -- act like school children when they arrive at the Temple of Apollo. Thus, unlike in Medea or Elektra, these women do not offer up terribly useful or sound advice. In addition, Euripides' narration begins with Hermes and ends with Athena -- both Apollo's siblings. Apollo never makes an appearance in the production, although he is seen as a puppet master, pulling the strings and making everything work out to his satisfaction. Which, as Athena explains, may not necessarily be to the humans' satisfaction. The god is looking at things from a century to century perspective desiring to create a family of rulers who will settle lands in his name, while the humans are viewing things from a day to day perspective designed to meet their own needs for safety and immediate gratification.

Translated by Deborah Roberts, this production offers a nice balance of humor and tragedy, as well as some intense monologues. The most difficult part of understanding the performance -- for those unfamiliar with Greek mythology -- are the poor acoustics of the space and the use of several different Greek names for the same deity. I highly recommend sitting in the first few front rows and reading Natural Theatricals' notes on the various gods' alternate names.

Director Brian Alprin utilizes the space of the main floor of the amphitheater to create an intimate theatre-in-the-round effect, the most compelling aspect of which is a huge statue of Apollo. With its back to the audience, Mr. Alprin purposely keeps Apollo's face out of the proceedings -- a symbolic reference to Euripides never bringing the deity directly into the play.

In keeping with the traditional retelling, Michael Null's set is a mix of temple and woods, while Rip Claassen's costumes are tunics and long robes, purple representing the color of royalty. Franklin Coleman's lighting is best put to use towards the end when the goddess Athena appears to the assembled cast.

As Ion, Michael McDonnell brings a warmth to the first half of the role, which makes his transformation into vengeful victim that much more jarring. Paula Alprin's Kreousa shines most when she is relating the story of her rape by the sun god. As King Xouthos, Manolo Santalla brings a self-absorbed shallowness to the ruler.

Also in the cast are: Tiffany Givens as sibling deities Hermes and Athena, Lucile O'C. Hood as Pythia, and Tom Neubauer as Kreousa's Old Tutor. The Greek chorus is made up of Jamie Boileau, Danielle A. Drakes, Samantha Merrick, Christina Pitrelli.

This production, with its traditional staging and costumes, will definitely appeal to those theatre goers who prefer their Greek tragedies -- even the happy ones -- not re-adapted to more modern times and settings. If you are following Washington's summer of Greek theatre, this production brings that traditional view to center stage.

|

ION by Euripides Translated by Deborah H. Roberts directed by Brian Alprin with Tiffany Givens, Michael McDonnell, Lucile O'C. Hood, Jamie Boileau, Danielle A. Drakes, Samantha Merrick, Christina Pitrelli, Paula Alprin, Manolo Santalla, and Tom Neubauer Set and Sound Design: Michael Null Lighting Design: Franklin C. Coleman Costume Design: Rip Claassen Running Time: 1 hour 50 minutes with one intermission A production of Natural Theatricals www.naturaltheatricals.com The Amphitheater of the George Washington Masonic National Memorial, 101 Callahan Drive, Alexandria Telephone: 703-739-5895 WED - SAT @ 8, SUN @ 2; $20 Opening 06/24/05, closing 07/17/05 Reviewed by Rich See based on 06/24/05 performance |

Gladiator

|

Do you ever have those days, when you feel you are damned? ---Gladiator |

E. Lucas

(Photo: Ian C. Armstrong) |

Writer and director Robert McNamara shows us how the savage gladiatorial killing contests were the reality TV shows of their time and the gladiators, themselves, were like rock stars and other celebrities today. Unfortunately for the gladiators, they usually died in a contest prior to age 35. Much like our own sports figures are put out to pasture around the same age.

And, most never reached more than 20 games before succumbing to an opponent. However, while they were playing they had the love, respect and sex of the blood thirsty and adoring masses. The nameless gladiator in Mr. McNamara's tale talks about the realities of life and death in Imperial Rome. Of training for the games, and how one learns to survive and conquer -- even one's friends and comrades in order to have one more "sweet breath of air."

Using the same set (by Michael Stepowany) as the previous installments, this production adds a metal chair, chrome case and a silver champagne stand to the stage. David Crandall's sound design features hard rock music to add to the WWF feel of the play.

Director McNamara has found an impressive hulking presence in actor Eric Lucas. Also Resident Playwright and Artistic Associate for Keegan Theatre, Mr. Lucas projects a larger-than-life aura that is compelling to watch. He appears much larger than he really is, as he swaggers about the Warehouse Theatre's small experimental space dressed in Alisa Mandel's lycra/leather outfit -- complete with leather cape and perfectly coiffed hair. In an ode to how the gladiators were the rock stars of their times, his makeup bears a striking resemblance to the rock group KISS, as well as some professional wrestlers of today.

Marianne Meadows lighting is most appealing when Mr. Lucas walks up to the on-stage microphone to embellish a point. The stage lights dim and a small pinpoint spot illuminates him in all his crazed echoing frenzy.

And that brings us to Mr. Lucas' performance which is part rake, part lost soul, part inflated sexual bravado. All hyper-masculinized in a steroid/amphetamine energized kind of way. Whether he is walking up the wall (literally) or slouched and sullen in his seat, he gives the appearance of a big predator cat, prowling the confines of his cage, waiting for his day of liberation. Waxing poetic about Death ("The Big D") or over his phallic "sword" or the phallic-likeness of his metal blade, Mr. Lucas gives an impressive, at times touching, performance.

Like its predecessors, Gladiator is a cerebral piece that requires one to listen attentively. There is a great deal of ribald humor in the script that you must listen to pick up. Unlike the previous two installments, you don't need to know as much about Roman history to get the allusions and references. In addition, the piece discusses parts of the Roman Games that they didn't talk about in high school, such as the sexual conquests of gladiators over wealthy "patrons." or the sizes of some of the professional fighters' genitals ("Maximus Dickus").

With his trilogy The Classics Made Easy, Mr. McNamara has provided us with an engrossing and enjoyable walk through the less glamorous aspects of ancient history. These intense and bawdy performances -- in repertory through July 17th -- are an intellectual treat.

|

Gladiator

Written and Directed by Robert McNamarawith Eric Lucas Set Design: Michael C. Stepowany Lighting Design: Marianne Meadows Sound Design: David Crandall Costume Design: Alisa Mandel Running Time: 1 hour 5 minutes with no intermission A production of Scena Theatre Warehouse Theater, 1021 Seventh Street, NW Telephone: 703-684-7990 WED - SUN -- in repertory, call for schedule; $25 Opening 06/21/05, closing 07/17/05 Reviewed by Rich See based on 06/27/05 performance |

The Persians

|

In my days of fear, I could hope. But then a thousand years of

happiness came and left me defenseless. ---Queen Atossa |

B. Hemmingsen and

K. Waters

(Photo: Ian C. Armstrong) |

The first surviving drama in Western culture, The Persians was written by Aeschylus in 472 B.C.E. eight years after the Greek-Persian battle at Salamis. The battle is in many ways a turning point for world history. Up until the end of the Persian Wars, the Persian empire ruled almost the entire known world. The Persians had attacked the Greeks; however the Greeks won the battle and eventually the war. Thus the Greek military superiority shown in Salamis ignited the melding of the Greek city-states and Athens as its center of culture and power. This eventually began the start of the Greek Empire and the Athenian chauvinism which eventually played a part in its decline.

Aeschylus had served with the Greek army during the battle and wrote the play from firsthand experience. However, he wrote The Persians from the losing Persian perspective. He did this for unknown reasons, but ostensibly to give Greek audiences a warning about hubris and the long standing consequences of war; as well as to humanize a people who were one-dimensionally characterized by the Greeks as a barbarian, power hungry people. Interestingly, Aeschylus himself was wounded in 490 during the Greek-Persian battle at Marathon.

Playwright Robert Auletta has taken Aeschylus' tale and melded it to our own country's struggle with Iraq. Thus the Persians (Iranians) have become Iraqis and the Greeks have become Americans (assisted by European allies). As I have said in other reviews of the Greek plays -- it's amazing how little has changed in 3000 years.

Written in 1993 after the first Gulf War, the play toured Europe extensively and was also mounted in the United States. Its depictions of modern day warfare are poignant and Mr. Auletta captures this with his vivid language and no-holds barred descriptions. It's obvious he has researched the "unofficial" accounts of the Gulf War, which our own government described at the time as a civilian casualty-free war. (In truth it is estimated over 100,000 civilian Iraqis perished in Operation Desert Storm.) The playwright should be applauded for his constant battering, in-your-face style which makes us, as Americans, mentally squirm. We want to wince every time the words "United States" or "America" are spoken. It is a moving piece that requires focused attention and demands putting aside patriotic illusions for 110 minutes to hear another side to a very dark tale. Suffice it to say, the play is hard for an American audience to watch and probably won't be mounted in Texas or any other red states very soon.

Following the same story line as Aeschylus, Mr. Auletta takes us to the royal court where Queen Atossa is conferring with her advisors. Her son King Xerxes has attacked the American empire and they await news of the battle. She and the advisors sense a coming doom, which is confirmed by the arrival of a messenger who describes the tragedy which he has only just barely survived. Having nowhere else to turn the Queen makes an offering to the gods and requests that they allow her dead husband Darius to return from the grave. Since Darius created the kingdom, she hopes he can provide some insight on how to save it from the onslaught of the "terrorists" who are attacking them. Darius does indeed return and Mr. Auletta, like Aeschylus, uses the time to show how the actions we take -- even ones that we forget about -- have consequences that can turn out to be deadly.

Having initiated a workshop presentation in 2003, director Robert McNamara and his team at Scena have been working on The Persians for over two years. Their effort pays off in a tautly paced, compelling story that keeps your attention the entire way through. A major feat for a show with no intermission that hits squarely at its audience's cultural contexts and flag.

Michael Kachman's set is a bombed out space in front of the tomb of King Darius. Fallen building parts, sand, a chalkboard with graffiti and a black oil slick on the floor set the stage. The oil slick has a child's toy hat sitting on it along side a dead blackbird. One wooden school chair is enshrined in light. The hat seems to speak to the folly of children's battles and the chair (a throne?) looks as if it is awaiting someone's return to sit in it. It could be for Queen Atossa, her son Xerxes, King Darius, or the American military rulers who are making their way to the city.

Marianne Meadows lighting is a varying array of blues and whites with an occasional orange gold overtone. David Crandall's sound design utilizes wind chimes, bombs, wind and a variety of eerie sounds to create the needed acoustic backdrop for this sad story. Alisa Mandel's costumes use royal purple and green for the Queen and her advisors. White for the death shrouded Darius. All are dressed in long flowing robes except for the messenger and King Xerxes who has arrived wearing a dead man's clothes so he can hide amongst the battlefield corpses.

Kerry Waters provides us a Queen Atossa who is fearful, in mourning and yet maintains an ability to see the comic irony in the worsening situation around her. Ms. Waters provides a touching and heartfelt performance of a woman who is a mother first and a queen second, even when her son is a megalomaniac psychopath bringing about the downfall of her nation. You see her flaws in the choices she makes, yet you wish her well because she senses the role she has played in this deadly situation.

Brian Hemmingsen shows us a King Darius who returns from the grave only to discover the weaknesses of his time as a man. Lavished with praise by his people, he was (in his own words) "not a father" to his son and this misjudgment has destroyed his legacy. Mr. Hemmingsen gives a strong, compelling performance of a proud and invincible man who has realized death can be avoided by no one and who discovers he, like everyone, is flawed.

David Bryan Jackson as the cowardly and demented Xerxes is alternately a little boy and an arrogant, delusional man. His mood swings and traumatized conversation style show the error of the Persian people for following such a leader. Thus the blame for the situation extends to everyone who has not made a point of opposing this cruel tyrant.

Eric Lucas' very moving performance as the messenger follows his recent, equally compelling role in Scena's one-man Gladiator. His distinct line delivery and haunted intonation work well as he describes the devastation he has seen and experienced. The only disconnect in the production though is Mr. Lucas' perfectly coiffed hair. While you are listening to him describe horrific sights, unconsciously you sense something is amiss. And surreptitiously it is. As the messenger he has just come through a devastating military battle held in a searing desert where bodies and tanks are being blown up by the force of the bombs. Apparently this messenger is using shellac because his hair is simply too American and too perfect when he arrives after crawling from the wreckage of the battle field.

This is the first show this summer to use an all male chorus, which is comprised of Dan Awkward, Kim Curtis, and Brian McIan. Starting out the play, as the audience walks into the space, they are lying on the floor seemingly asleep. When the action commences they shout their words that defy the American army and its European allies. It becomes obvious this is more bravado than belief, as they begin to suspect that all at the battle does not go well. As the drama unfolds it soon is apparent that they too have played a part in Persia's decline with fawning advice to Xerxes designed to protect their own lives over the life of their country. The three actors blend well and create a unified vocal presence.

If you are interested, Shakespeare Theatre will be mounting its own version of The Persians next April and comparing the two could be very interesting. Meanwhile, Scena Theatre's production, which is only the second time Mr. Auletta's version of The Persians has been produced in the United States, accomplishes what theatre does best. It makes us question our world, look inside ourself and discover our own inner truth about our feelings. And it provides a warning that what comes around goes around and karma has away of coming back at us in triplicate. So run, don't walk to get a ticket -- and take a friend with you.

|

The Persians

by Aeschylus, adapted by Robert AulettaDirected by Robert McNamara with Dan Awkward, Kim Curtis, Brian Hemmingsen, David Bryan Jackson, Eric Lucas, Brian McIan and Kerry Waters Set Design: Michael Kachman Lighting Design: Marianne Meadows Sound Design: David Crandall Costume Design: Alisa Mandel Running Time: 1 hour 50 minutes with no intermission A production of Scena Theatre GALA Tivoli Theatre, 3333 14th Street, NW, Washington DC Telephone: 703-684-7990, http://www.scenatheatre.org THU - SAT @8, SUN @3; $25 Opening 07/16/05, closing 08/14/05 Reviewed by Rich See based on 07/16/05 performance |

Easy-on-the budget super gift for yourself and your musical loving friends. Tons of gorgeous pictures.

>6, 500 Comparative Phrases including 800 Shakespearean Metaphors by our editor.

Click image to buy.

Go here for details and larger image.