SITE GUIDE

SEARCH

ADVERTISING AT CURTAINUP

REVIEWS

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

New Jersey

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

Writing for Us

A CurtainUp Los Angeles Review

R. Buckminster Fuller: The History (and Mystery) of the Universe

|

We have a choice of Utopia or Oblivion! &mdash R. Buckminister Fuller

|

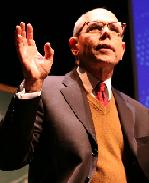

Joe Spano as R. Buckminstger Fuller

(Photo: )

|

It begins simply enough, with family photos of Fuller as a young child. Nearly blind, he would listen to his older sister reporting on what she saw of the world around them. Thinking she was making it up, he would reciprocate with fantasies of his own. At 4Ĺ he was finally outfitted with glasses and the world became clear to him. But the childlike wonder and imaginative vision remained with him for the rest of his life.

As a young man, he was "dismissed" from Harvard, not once, but twice, and began to formulate his philosophy based on the need to think for himself. "I needed to rethink everything I knew," he explains. He developed a theory that "a human being is a pattern of integrity," and another that postulated that "all natureís patternings are based on triangles." Caught up in examining the ramifications of his theories, both geometrically and metaphysically, he scarcely spoke for two years which must have been hard on his wife and two daughters.

Fuller's career included a stint in the Navy in World War I, failing in business, and being derided as a lunatic by the scientific community. In the depths of depression afterhis beloved older daughter died, he contemplated suicide. However, he talked himself out of it with the realization that our greatest trespasses result from "the feedback of our own negativity" and that "the highest form of integrity is admitting our mistakes."

"We are here for each other,"Ēhe declared, and set about to convince the world of his utopian vision that as we all learn to "do more and more with less and less", there will be more than enough for everyone. He called this concept "ephemeralization," a product of synergy or collaboration to achieve a common goal. As he explained, "My goal was never to make money.Trying to make money and trying to make sense are mutually exclusive."

Making sense of his own life also seemed to be a personal goal. To that end Fuller created what he called the "Dymaxion Chronofile," a series of journals that documented his life every 15 minutes from 1915 to 1983 and included correspondence, bills, notes, sketches, and clippings from newspapers, producing what has been said to be the most documented human life in history.

Fuller also had a personal concept of God as a "phantom captain" with "an awareness of perfection, unity, infinity, eternity, and truth." In pursuit of Godís basic truth, he asked himself, "Is there a structure that is common to both physical and metaphysical reality?" Then, demonstrating with a series of classroom props and a blackboard, Fuller/Spano comes to the conclusion that the triangle is the basic structure, "and the only stable structure" in the universe. Based on this insight, Fuller created his famed geodesic dome, a structure composed of various squares and triangles held together by tension rather than by pillars, buttresses and other traditional constructions. He called this development "vector equilibrium," a balance between outward thrust and restraining force, and in time his innovative, lightweight, and easily constructed domes came to cover more square feet of the planet than any other single kind of shelter.

Bringing the concept of synergy to bear on the act of problem-solving, which, he noted, "is common to all humans," he urged all people to work together for the common good before itís too late. "There is enough for all," he insisted, adding prophetically, "We have a choice of Utopia or Oblivion."

R. Buckminster Fuller: The History (and Mystery) of the Universe is an intellectually challenging, thought-provoking boggle of the mind. D.W. Jacobs, who directed as well as authored this expansive and expanded production, set it in the form of a college lecture, effectively putting Joe Spano through his didactic paces. But if Spano provides the meat and potatoes, the frothy dessert is provided by scenic designer David Cuthbert and lighting and projection designer Jason H. Thompson. Within the confines of the classroom set, a gigantic background screen periodically flashes on some of the most fascinating illuminations imaginable: universes and diagrams and shimmering photographs of all kinds.

Still, I canít help but smile, thinking of the judgment a dear friend of mine would probably make of this production. I can just hear him say "Itís very good . . . but itís not Mamma Mia!"

|

R. Buckminster Fuller: The History (and Mystery) of the Universe Written and Directed by D.W. Jacobs Cast: Joe Spano (R. Buckminster Fuller) Set Design: David Cuthbert Lighting and Projection Design: Jason H. Thompson Costume Design Darla Cash Sound Design: Luis Perez Running Time: Not given; includies one 15-minute intermission Rubicon Theatre Company, Rubicon Theatre, 1006 E. Main Street, Ventura, (805) 667-2900, www.rubicontheatre.org From 01/17/08 to 02/10/08.; opening 01/19/08 Tickets: $29-$52. Seniors (65+) and military personnel save $5. Students with ID, $20. Reviewed by Cynthia Citron on January 20, 2008. |

Easy-on-the budget super gift for yourself and your musical loving friends. Tons of gorgeous pictures.

Leonard Maltin's 2007 Movie Guide

>

>