SITE GUIDE

REVIEWS

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

New Jersey

DC

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

Writing for Us

A CurtainUp  London Feature

London Feature

London Feature

London FeatureThe Big Brecht Fest

The Young Vic is hosting a festival to celebrate some of the early works by Bertolt Brecht in the wonderfully wit-synched The Big Brecht Fest (pun courtesy Rory Bremner). It is a tribute from the Artistic Director of the Young Vic, David Lan to Bertolt Brecht a playwright he much admires, but whose early work is neglected, although the famous plays like The Caucasian Chalk Circle, Mother Courage, Galileo and The Good Woman of Setzuan, are produced frequently. The four early plays that make up the festival are freshly translated and staged in the studio spaces, the Maria and The Clare in the theatre's new building in Waterloo's The Cut. First is the double bill of A Repectable Wedding (1919) in a new version from British comedian Rory Bremner and, from playwright Martin Crimp, The Jewish Wife (1938). Later the festival will pair Señora Carrar's Rifles (1937) translated by Biyi Bandele and How Much Is Your Iron? (1938) from Edna Walsh.

*A Respectable Wedding (1919) | *The Jewish Wife (1938) | *Senora Carrar's Rifles (1937)|*How Much Is Your Iron? (1938)

Editor's Note: An * asterisk will be aded to each title as reviews of the plays are posted.

Editor's Note: An * asterisk will be aded to each title as reviews of the plays are posted.

How Much Is Your Iron?

|

Iron for Sale. 1938. So fade the lights, begin the game.

---- The Narrator

|

Joseph Alford as Svendson and Elliot Levey as The Customer

(Photo: Stephen Cummiskey) |

It is a simple allegory but effective for all that staged in the tiny Clare Studio. A massive iron pipe dominates the set, looking as if it has been thrust through the wall, a reminder that without iron, countries cannot manufacture armaments and ships and guns and aircraft and bombs. Before the play even starts, the designer has created a wonderful surrounding. The floor is covered in red earth, thin trunks of silver birch, and on a table arranged in a stepped pyramid and lit mysteriously, a pile of small iron ingots.

The Customer is the figure of Germany and has a persuasive and bullying insistence in his negotiations with the Swede. "Don’t be seduced by fear", he tells Svendson and then he shouts suddenly and everyone jumps in fright. In 1939 Frau Czech becomes increasingly desperate to sell her shoes, she tells us how Herr Austrian was attacked and slaughtered but the Swedish businessman stays neutral and carries on his lucrative business. Later in a chilling scene, the Customer offers those same shoes, covered in blood which the Swede wears and gets blood not just metaphorically on his hands but also literally on his feet.

Edna Walsh’s new translation is a lively piece and some fine acting brings her text to life. Underneath the jokey veneer are the politics of aggression. Joseph Alford’s serious shopkeeper who exercises using iron bars as gym weights personifies the neutrality that continues to trade with the Third Reich. Elliot Levey is marvellous in his wide boy, brown striped suit as The Customer who is determined to get exactly what he wants, disguising violence with a ready patter to suggest that Frau Czech died in his arms when he was protecting her from her neighbours.

In the final scene we hear in the distance the sound of cannon fire as the Swede is forced to hand over his iron bars. Brecht wrote this after he had fled from Germany to Denmark after his writing was banned as "decadent" and it was staged in Stockholm in 1938 in an effort to sway Swedish public opinion. The double bill with Señora Carrar’s Rifles works effectively as both plays have themes which resonate with each other as issues in Europe in the 1930s.

|

HOW MUCH IS YOUR IRON?

Written by Bertolt Brecht Translated by Edna Walsh Directed by Orla O’Loughlin With: Elliot Levey, Naomi Fredericks, Michael Colgan, Joseph Alford, Kevin Colson Design: Dick Bird Lighting: Jon Clark Sound: Gareth Fry Running time: 35 minutes with no interval Box Office: 020 7922 2925 Booking to 5th May 2007 in a double bill with Señora Carrar’s Rifles ie. Ticket gives admission to both shows Reviewed by Lizzie Loveridge based on 24th April 2007 performance at the Young Vic, The Cut, London SE1 (Rail/Tube: Waterloo, Southwark) |

Señora Carrar’s Rifles

|

We’re living on a broken plate.

---- Pedro |

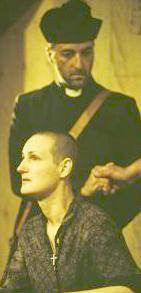

Sandy McDade as Señora Carrar and Antonio Gil Martinez as Father Francisco

(Photo: Stephen Cummiskey) |

The predicament in this play is that of a widowed mother (Sandy McDade) who has lost her fisherman husband and who wants to protect her two sons from joining the fighting. She refuses to engage on either side resisting the arguments of her Republican brother that her inaction supports Franco’s Nationalist cause. The motivation for the visit from her brother Pedro (Richard Katz) is the rifles she has hidden under the floorboards. She is also visited by an old woman, Señora Perez (Jane Guernier) who has lost children in the cause and who has the ignominy of her son Francisco joining the Republicans, whom she has disowned. Señora Carrar is also under pressure from the pacifist priest Father Francisco (Antonio Gil Martinez).

Paul Hunter’s production is full of fine detail, effective switches of lighting and even witty staging. The set has a sloping roof to the Carrars’ house and an oven in the wall for baking bread through which comes the broadcast in Spanish of the campaigning, medal wearing General (Aitor Basauri) who, in another speech, appears above the house with the roof as his podium. The Widow Perez enters diffidently unsure as to where she might be permitted to sit confused by the upended table under which are the concealed rifles. When they describe the discovery of Señor Carrar’s body, a twisted sheet is carried in soaked in blood, the lighting dimmed as memory.

It is Sandy McDade’s performance which dominates the powerful acting. With her hair shorn, she shows the desperation of a woman determined to keep her sons alive. When trying to persuade her younger son (Hugh Skinner) to stay at home she promises him anything pulling out every weapon in her armoury, "You can smoke if you want, " she says. The scenes where Richard Katz as her principled brother tries to change her mind are very well played. Who could forget her anguished expression as she decides not only to allow her son to go, but to join the war herself?

|

SEÑORA CARRAR’S RIFLES

Written by Bertolt Brecht Translated by Biyi Bandele Directed by Paul Hunter Starring: Sandy McDade With: Aitor Basauri, Jane Guernier, Richard Katz, Antonio Gil Martinez, Celia Meiras, Hugh Skinner Design: Robert Innes Hopkins Lighting: Mischa Twitchin Sound: Ian Dickinson Running time: 50 minutes with no interval Box Office: 020 7922 2925 Booking to 5th May 2007 in a double bill with How Much Is Your Iron? ie. Ticket gives admission to both shows Reviewed by Lizzie Loveridge based on 24th April 2007 performance at the Maria, Young Vic, The Cut, London SE1 (Rail/Tube: Waterloo, Southwark) |

The Respectable Wedding

|

When is it due?

---- Young Man to the Bride |

Scene from A Respectable Wedding.

(Photo: Stephen Cummiskey) |

We are assembled in a tiny flat for the home based reception after the wedding of Russell Tovey's Groom and his very pregnant bride (Jemina Rooper), with all the embarrassment of a maladroit best friend (James Corden), who puts his foot in it on every occasion while trying to be nice. A father (Lloyd Hutchinson) whose longwinded and gruesome stories about vomiting or disease puts everyone off their wedding breakfast and has the whole cast facing front and glazing over with polite boredom as we wait for him to get to the punchline. When the joke arrives it seems sadly lacking and certainly not worth the rigmarole. Then there is the ultra thin Wife (Doon MacKichan), fresh from a spray on tan at the salon, rivalling the bride in her stiff white minidress with a silly two feather hat, who is bickering with her morose husband (Martin Savage). Together they give you every reason never to get married.

We are told that the Groom has built the furniture himself and in the course of the hour it hilariously starts to fall apart. The backs come off chairs, legs off tables, doors off cupboards, seats fall through and people get stuck in the chair frames. The neighbour from downstairs (Kobna Holbrook-Smith) makes a speech thanking the man who made it all possible, Jesus Christ, and leads everyone in a hymn which they gamely try to join in with, although they obviously know neither the words nor the tune. The sister (Hayley Bishop) has a quick shag in the kitchen with the Young Man behind the partition. There is trashy music and wonderfully choreographed dances as the Groom tangos with the Wife, much to the chagrin of his new wife, the Bride. The mother keeps wheeling in the food, crème brulees on top of chocolate mousse and cod mornay! When they troop off to view the home made bed, a flash and loud bang indicates that the Groom's ability as an electrician is as abysmal as his carpentry talent and the flat is plunged into darkness. Russell Tovey is of course delightful as the hapless groom with his Tintin quiff and cute expression.

All this takes place in a cramped suspended box set maybe ten feet by eight. A Respectable Wedding is a gem, a witty farce, fresh as a daisy, brilliantly directed and deserves a much longer run so that many more people can go out into the night laughing.

|

A RESPECTABLE WEDDING

Written by Bertolt Brecht Translated by Rory Bremner Directed by Jo Hill-Gibbins With: James Corden, Flaminia Cinque, Russell Tovey, Kobna Holdbrook-Smith, Jemima Rooper, Lloyd Hutchinson, Doon Mackichan, Hayley Bishop, Martin Savage Design: Ultz Lighting: Mischa Twitchin Sound: Paul Arditti Movement: Clive Mendus Running time: One hour 10 minutes with no interval Box Office: 020 922 2925 Booking to 14th April 2007 in a double bill with The Jewish Wife ie. Ticket gives admission to both shows Reviewed by Lizzie Loveridge based on 4th April 2007 performance at the Young Vic, The Cut, London SE1 (Rail/Tube: Waterloo, Southwark) |

|

What is it that I am doing to them? I'm a typical middle class woman with servants and so on. . . . They have invented a new way of scoring and now it turns out that I am one of the ones with zero. Well it serves me right!

---- Judith |

Sean Jackson as the Husband and Anastasia Hille as the Wife

(Photo: Stephen Cummiskey) |

Set in an affluent 1930s bedroom with its satin finish wood bedroom suite, matching wardrobes, dressing table with huge circular mirror, a woman (Anastasia Hille) packs ready for a journey. She has seven or more items of matching cream leather luggage and she is agitated, smoking and nervously packing her clothes and wrapping up her precious belongings. She looks long and hard at the photographs in frames before she packs them. She has her hair pinned under a chiffon scarf while the style sets.

The woman makes phone calls to cancel her commitments, first to the people she plays Bridge with, then to some people she wants to come to dinner next week to keep her husband company, to her sister-in-law and to a friend. We can hear her irritation as she talks to the people she is leaving behind. She tells them she is going to Amsterdam for a few weeks, but it is obvious from the quantity of luggage she will never be coming back and that is if she is lucky enough to get to Amsterdam which, even if she does, we know will not eventually be a safe place.

It is quite an unsympathetic portrait of this woman. She sounds so tetchy and querulous on the telephone we do not warm to her although with our knowledge of history we know what her terrible fate will be if she remains in Germany. We start to get glimpse of the difficulties she is encountering in Germany in the 1930s. She is being shunned because she is Jewish and her husband, a Gentile, is suffering professionally for his choice of a Jewish wife. She places her husband's photograph on a chair and addresses it as if she is talking to him, rehearsing telling him why she is leaving.

So why do we not feel immense sympathy? Is it the expanse of her material possessions? The jewellery, the designer clothes, the silk undergarments? The lack of children? It is only at the end of the play when she sinks to the floor like a discarded frock, out of view, and we hear the sound of a steam train we know that she is probably on her way to a concentration camp and subject to, if not death, terrible privation, that we can feel distress. What this play seems to do is to cast us as the uncaring German people, the ones who claim not to be aware of what was happening.

Anastasia Hille is perfectly cast, tall, elegant and not at all a warm personality. There is no humour, no lightness or irony. She is a Jewish woman within a Gentile context with no family to support her. She obviously had fallen out with her husband's sister. Did her family disapprove of her choice of husband? Her husband (Sean Jackson) appears for the last few minutes of the play, and as he hands her a winter coat, it is apparent that he knows she will be going longer than a few weeks. An interesting play but an incongruous pairing with the frivolity of A Respectable Wedding.

|

THE JEWISH WIFE

Written by Bertolt Brecht Translated by Martin Crimp Directed by Katie Mitchell With: Anastasia Hille, Sean Jackson Design: Hildegard Bechtler Lighting: Jon Clark Sound: Gareth Fry Music: Paul Clark Running time: 45 minutes with no interval Box Office: 020 922 2925 Booking to 14th April 2007 in a double bill with A Respectable Wedding ie. Ticket gives admission to both shows Reviewed by Lizzie Loveridge based on 4th April 2007 performance at the Young Vic, The Cut, London SE1 (Rail/Tube: Waterloo, Southwark) |

|

London Theatre Tickets Lion King Tickets Billy Elliot Tickets Mary Poppins Tickets Mamma Mia Tickets We Will Rock You Tickets Theatre Tickets |