SEARCH

REVIEWS

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

LA/San Diego

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

On TKTS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

Writing for us

A CurtainUp Review

Waiting For Godot

|

What did we do yesterday? --- Vladimir In my opinion we were here. ---Estragon |

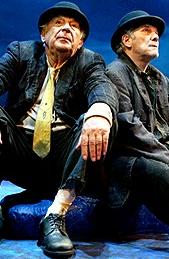

Sam Coppola & Joseph Ragno in

Waiting for Godot

|

There are probably as many ways to wait for Godot as there are theories on who or what Godot really is. If you believe that Godot is a theatrical fraud because you think that it has no plot, no point, no purpose, and no progression of activity, then the production being presented at the Theater at St. Clements isn’t likely to change your mind. That this production also isn’t any fun won’t help win any prospective converts.

Purists, need not worry that the enigmas of the play have been made any clearer here than they ever were, or that the riveting text is appraised in a new light. Yet there are moments that suggest a sly and skewed take on this existential masterpiece that will keep the devoted in their seats, a decision that was not shared by about twenty of the sixty or so patrons at intermission (the theater has 151 seats).

Given the restrictions and demands imposed upon its interpreters by the guardians of Beckett-land, the staging by Alan Hruska certainly remains essentially faithful if not especially mindful of the rhythms that propel the precise text. With its artfully terse dialogue creating its own inimitable reductionist plot, the play’s simple contrivances tend to emerge and submerge with timeless abandon. I would respectfully suggest that Hruska, who has fearlessly chosen this formidable work as his debut in theatrical directing, has yet to develop either an ear for the rhythms of people bickering and baiting or an eye for pacing. One can detect in the actors a noticeable attempt at motivation (an ill-advised adornment to any absurdist work) that can probably be attributed to a production originally developed at the Actors Studio.

If Hruska’s vision can be considered academic at best, the players are simply stranded between the play’s humor and its utter poignancy. Within this context, we find two shabbily attired men, although both sport dapper though dusty derbies in an apparently on-going, protracted, (hopefully) funny, discourse and going nowhere in particular. The two impatient tramps, that spend their arguably precious life and time near an almost barren willow tree waiting for the arrival of an elusive Mr. Godot, are played by Sam Coppola (Vladimir) and Joseph Ragno (Estragon). Except for the intrusion into their bleak existence by a despotic master and his obedient slave, Estragon and Vladimir may or may not be aware at any point that their mutually entwined karmas are leading them all to the same place.

At the outset, their appearance may evoke faint memories (for some) of Smith and Dale, or even Laurel and Hardy, but they fail to capitalize on this in the manner of true vintage vaudevillians. Their inability to jiggle the balance of power leads to tedium. As a result, whatever conflict there is between these eternally bonded characters becomes monotonous. As Vladimir, Coppola has chosen not to broaden the many opportunities for burlesque, however racked as he is with discomfort from malfunctioning kidneys. That would be an okay decision if Coppola’s performance didn’t lose focus. The part’s subtle nods to his sophistication warrant more agitated changes than Coppola provides. Nevertheless, he validates his presence as a certifiable crutch to his befuddled buddy. There is unfortunately not enough despairing resolve in Ragno’s performance as Estragon, whose soulful paranoia is only fitfully realized.

Waiting and waiting and waiting, both Go Go and Di Di (as they are familiarly known to each other) are characters we are concerned about and really care about, a situation all too rare in much contemporary dramatic literature. The punch that the play normally gets with the intrusion of the whip-snapping master Pozzo is notably disappointing. As portrayed by Ed Setrakian, Pozzo is less a terrorizing autocrat than a self-important fool. As a result, his self-betrayal remains conspicuously unmoving. A pasty-faced Martin Shakar chokes wheezes and shakes and makes a loquacious case for his pathetic plight as the abused and humiliated and luckless Lucky.

In all fairness, Shakar does get behind the pain in his lengthy gobbledygooked-up soliloquy, something that cannot be said of the others. Tanner Rich effectively played the role of Boy. Set Designer Kenneth Foy’s oval playing area contains the obligatory tree and flat rock nicely backed by a blue skies cyclorama artfully lit by Paul Miller. Ann Hould-Ward’s costumes provide the essentials: ratty, ill-fitting clothes.

Waiting for Godot appears to have a secure and resounding life of its own, no matter how diverse or even perverse the interpretation. Next year will celebrate the 50th anniversary of the play’s Broadway premiere. Will that inspire the definitive version? Probably not, but that makes it all the more inviting.

Godot was first presented as En Attendant Godot at the Theatre de Babylone, Paris, France during the season of 1952-53. It had its Broadway premiere at the John Golden Theater on April 19, 1956 and played through June 9 for a total of 59 performances.

| WAITING FOR GODOT Playwright: Samuel Beckett Directed by Alan Hruska. Cast: Sam Coppola (Vladimir), Joseph Ragno (Estragon), Ed Setrakian (Pozzo), and Martin Shakar (Lucky). Set Design: Ken Foy Costume Design: Ann Hould-Ward Lighting Design: Paul Miller Running time: Approximately 2 hours and 30 minutes, including one intermission. Actors Studio, at Theatre at St. Clement's,423 West 46th Street (9th/10th Avenues), 212/239-6200 From 11/16/05 to 1/17/06--closing early on 01/01/06; opening 11/16/05 Tue - Sat at 8pm; Sat at 2:30pm; Sun at 3pm Tickets: $55 Reviewed by Simon Saltzman based on November 29th performance |

Leonard Maltin's 2006 Movie Guide

Leonard Maltin's Classic Movie Guide

>6, 500 Comparative Phrases including 800 Shakespearean Metaphors by our editor.

Click image to buy.

Go here for details and larger image.