SITE GUIDE

REVIEWS

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

New Jersey

DC

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

Writing for Us

A CurtainUp Review

Conversations in Tusculum

by Les

Gutman

|

What if there's no Republic left? What if they destroy it while we're being patient? What if there's nothing left to preserve? What if while we sit here -- they continue, as they have, inch by inch, brick by brick, to take apart everything? While we sit and read, and we write our books, put on our plays, make money, talk about real estate, fish -- everything -- gone. And we have nothing. There is nothing left. Worth living for!!—-Brutus

|

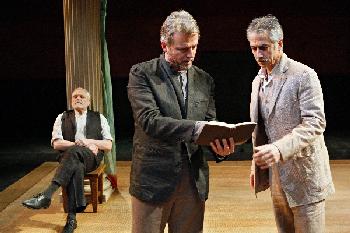

B. Dennehy, A. Quinn and D. Strathairn

(Photo: Michal Daniel) |

The year is 45 B.C., it is summer, and the place is Tusculum, ancient Rome's version of the Hamptons. There, Richard Nelson sets this back story to what we already know about Julius Caesar, who will meet his end on the next Ides of March. The play centers on Brutus (Aidan Quinn), Cassius (David Strathairn) and Cicero (Brian Dennehy). It does not require a soothsayer to discern that Nelson intends some resonance in contemporary America from what he writes.

Finding relevance in Caesar's downfall is, of course, nothing new. What Nelson seeks to gain by shifting the focus from the public oratory to these private conversations is a cautionary tale about the need to avoid complacency. (See quote above.) What he loses, however, is a great deal of what makes the story compelling.

At its best, most of which does not arrive until the second act, Tusculum informs the forward drive of Caesar's foes, which eventually manages to develop some action and even dramatic heft; for far too much of the play, inexplicably, Nelson dwells on what, in contemporary terms, would be more likely to appear on Page Six of the Post than the OpEd page of the Times. And it is slow going.

Nelson gives us glimpses of the influence of Cato (the incorruptible pol on whom the John McCain character is modeled in current politics), who committed suicide in the previous year, enough so that one might have wished for a play that included more of him. Instead, we get gossip -- sometimes endless conversation about domestic troubles we really don't care about. At times, it feels like the experience of sitting in a restaurant, eavesdropping on the large gathering at the next table, trying for a few minutes to figure out who's who and what they are saying, until you lose interest. Brutus's wife Porcia (Gloria Reuben), who is also his cousin, was Cato's daughter. His mother, Servilia (Maria Tucci), was Cato's sister. Cassius is his brother-in-law. Cassius's wife (that would be Brutus's sister) has been seized by Caesar, to be his lover, a feat he achieved with an assist from Servilia, much to the chagrin of, well, just about everyone. So what?

Both women perform very well, Ms. Tucci especially so. Unfortunately, they are superfluous here. How much better a play this would have been had the playwright delivered a compact piece instead of the overwrought one we got. In the end, what we have is a potentially fine play blown out of proportion.

The men at least get to spend part of the play talking about matters of substance, like the future of their world. Cicero is by far the most abstract, but Dennehy grounds him in a fine performance. A generation older than Brutus and Cassius, he is nonetheless clear in his admonitions. But if there is a revelation, it is Aidan Quinn, who has (not counting a pair of glorified readings, Salome and The Exonerated) not appeared on stage in the last twenty years. He is an astonishingly engaging and forceful stage actor, giving Dennehy a true run for his money, and running circles around the well-regarded Strathairn. When Nelson finally lets them get down to business, things get pretty exciting. It's getting to that stage that is the trouble. For the record, the cast also includes Joe Grifasi as Syrus, an itinerant actor providing entertainment in exchange for food and lodging.

Tha Anspacher's classical columns and balustrades form a perfect setting for this play, and set designer Thomas Lynch wisely works with a light touch, adding only a hempish floor covering and a pair of simply-drawn curtains plus a smattering of stools and benches. Susan Hilferty's costumes, consistent with the tone of the play itself, find a suitable no-man's land between classical and contemporary, apt for a bit of relaxed summering, no matter the pending stakes. Jennifer Tipton has left all of her experimental bag of tricks at home this time, rendering the changing summer light just as it ought to be. John Gromada's sound design, aside from some musical entertainment courtesy of an ocarina, consists mostly of the sorts of bird-chirping and dog-howling you would expect on a summer day at an Italian villa.

Although I am not enamored of writers who indulge themselves by directing their own work, Nelson's technical efforts here are just fine. But my point is underscored. Would that there had been someone here to ask the writer to justify his words.

|

Conversations in Tusculum

Written and directed by Richard Nelsonwith Brian Dennehy, Joe Grifasi, Aidan Quinn, Gloria Reuben, David Strathairn and Maria Tucci Set Design: Thomas Lynch Costume Design: Susan Hilferty Lighting Design: Jennifer Tipton Original Music and Sound Design: John Gromada Running time: 2 hours, 25 minutes with 1 intermission Public Theater (Anspacher), 425 Lafayette (Astor Pl/E. 4th St) Telephone (212) 967-7555 Opening March 9, 2008, closes March 30, 2008 TUES and SUN @7, WED - SAT @8, SAT @2, SUN @3 (no performance 3/11 or 3/18); $25-50, students $25, rush $20 (1 hour prior to curtain, cash only) Reviewed by Les Gutman based on 3/6/08 performance |

Easy-on-the budget super gift for yourself and your musical loving friends. Tons of gorgeous pictures.

Leonard Maltin's 2007 Movie Guide

At This Theater

Leonard Maltin's 2005 Movie Guide

>

>