SEARCH CurtainUp

On TKTS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

REVIEWS

FEATURES

ADDRESS BOOKS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

DC

NEWS (Etcetera)

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

DC (Washington)

London

Los Angeles

QUOTES

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

Type too small?

NYC Weather

Small Craft Warnings

by David Lohrey

|

The act of love is like the jabbing of a hypodermic needle. . . ---Quentin |

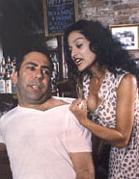

Michael Surabian, Elise Stone

(Photo: Gerry Goodstein) |

Williams wrote this play at a low point in his career as a writer. Broadway, the Shuberts, and the New York critics were not in the mood to indulge their favorite son. For a man who needed to be loved, this rejection was not easy to take. As Williams himself wrote in Night of the Iguana, "Nothing disgusts me unless itís unkind, violent." The behavior of the critics in this period was unkind; their criticism was, unforgivably, often violent. It is perhaps not for nothing that Small Craft Warnings is largely about betrayal, and a note of disgust can be heard in the authorís otherwise compassionate voice.

There is much to admire in this production, but it cannot hide the play's fatal flaws. The "old lightning," to use Williams' own term, is missing, but that should perhaps be obvious for a play set largely in a fog. Taverns, real or imagined, may offer writers an inviting setting for social gatherings, but do not provide easy opportunities for dramatic conflict. Escape comes with the swing of the saloon door, while drama thrives where escape is impeded. Peopled as this play is with drifters, when the going gets tough, it is too tempting for them simply to walk out. As in a Greek tragedy, all of the violence takes place off-stage and, one imagines, the best occured long before the play opens. What violence does unfold Ė a street brawl and a botched abortion Ė lacks dramatic purpose beyond giving its participants an excuse to head for the hills.

This is a play stitched together, rather than driven by a single dramatic action. Monk (Craig Smith), the sour tavern keeper, clings desperately to his dream of running a "clean" shop, free of the kind of rough trade apt to attract the attention of the local mob or police. He doesn't want the "boys" going to the toilet in pairs, but doesnít mind it when Violet (Kathryn Foster) gives Bill (Michael Surabian) a hand-job beneath the table. Violet doesn't say much and doesn't have much going for her, but her sexual manipulations, literally, are what set off Leona (Elise Stone) in what must be one of the most sustained tirades in modern dramatic literature. Ms Stone plays Leona as if she alone could provide the lightning missing from the playís core.

Out of the mist (provided throughout the evening by great gusts of stage smoke) comes this whirlwind of female invective, but as in any storm at sea, there is nothing for the lightning to strike. Bill, a man who admits to having only one thing to offer the world (located between his legs), seems perfectly content with Violetís attentions. Monk is an oddly sexless creature, at once wretched in his loneliness, yet too prim for human contact. Doc (Harris Berlinsky), who in the opening scene strikes one as an interesting, rather Chekhovian character, all but disappears, only to return in the last scene to give us something to feel sad about. Poor Leona hasn't a hope in hell of finding a man in this dump. She's Blanche without a Stanley. Nobody wants to rape her; there's nobody in the bar whose eyes are worth scratching out. By the time a gay couple walks in, she's appointed herself the resident good listener; only the "boys" don't want to patch things up. Quentin (Jason Crowl), who prefers straight men, has picked up a hitchhiker (Edward Griffin) from Iowa who, God forbid, happens to be gay.

We pretty much know by this time that the play is going nowhere, but when Mr. Crowl opens his mouth, things begin to pick up. What a voice. It wouldnít matter whose lines this guy was given, his silken voice would turn them into poetry. Lucky for us, he has some of Williams' best writing to recite, even if it is not especially dramatic. Dressed in loose casuals, Mr. Crowl plays his role as the perfect embodiment of California decadence. He walks with his center of gravity placed just south of his waistline, giving him a marvelous air of sexy indolence. The women may not notice, but even the heterosexual Bill sits up straight when Quentin saunters by. He actually resembles Tennessee Williams, which is a good thing, because it's a fair bet that Quentin is a younger Williams, only the author has given the character the voice of experience he most certainly lacked when he was a young writer in Laguna. In one of Williams' most confessional monologues, Quentin reveals much about gay life, but focuses especially on the way promiscuity corrodes desire. Williams creates a fascinating portrait of the debased romantic hero, a part that should properly be at the center of this play.

Michael McKowen's seedy bar works, evoking at once the real and unreal aspects of Williams' vision. Giles Hogya's lighting is instrumental in taking the audience back and forth between public and private, giving the play its proper sense of lives lived largely in the imagination. Finally, Scott Shattuck's direction challenges the audience to find meanings otherwise lost in the haze of the authorís uneven writing. This is one play where a lack of clarity is desirable. The cast, really an ensemble, delivers the message the play seems most intent on communicating: we are always alone, but most especially with other people.

Editor's Note: For an overview of Tennessee Williams' Career and reviews of his plays reviewed at CurtainUp (including the Worth Street Theater Company's production of Small Craft Warnings, see our Authors' Album

|

Small Craft Warnings

Written by Tennessee Williams. Directed by Scott Shattuck. Cast: Kathryn Foster, Harris Berlinsky, Craig Smith, Michael Surabian, Elise Stone, Christopher Black, Jason Crowl, Edward Griffin. Set Design: Michael McKowen Sound Design: Sam Kusnetz Lighting Design: Giles Hogya Costume Design: Susan Soetaert Running Time: Approximately 120 minutes, with one 15-minute intermission Jean Cocteau Repertory, 330 Bowery, (212)-677-0060 Wednesdays at 7pm, Thursdays through Saturdays at 8:00, and Sundays at 3:00pm 8/24/01-11/15/01 Reviewed by David Lohrey based on 9/23 performance |