SITE GUIDE

SEARCH

REVIEWS

REVIEW ARCHIVES

ADVERTISING AT CURTAINUP

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

New Jersey

DC

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

A CurtainUp Review

Oroonoko

By Kate Shea Kennon

|

Have you too come against me?— Oroonoko to Trefry

|

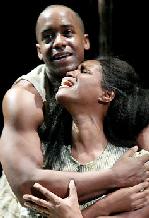

Albert Jones and Toi Perkins in Oroonoko

|

review continues below

The U.S. premiere of Mr. Bandele's adaptation lifts Oroonoko out of its limitations as an early travel narrative and at the same time lifts its title character out of its shallow aspect as the "noble savage." Echoes of Shakespeare reverberate throughout and Bandele exploits Behn's literary relationship to her predecessor to the play's obvious success. In setting the first act of the play in Africa, Bandele stresses a specific experience in contrast to the archetypes of some of Europe's most famous dramatic characters.

Back when Aphra Behn wrote her Oroonoko, novellas did not exist as a genre. Who wrote the very first novel is under discussion, but Behn undisputedly is the first female author to make a living from her writing. Mr. Bandele's stated ambitions for this adaptation were to fix the "obvious inaccuracies" of Behn's Africa. Certainly there would be room to do so since the extent of her travels in the 17th century are questionable. In Bandele's Oroonoko Africa is beautifully characterized through West African costume and dance. Even small moments such as the "walk to the ancestors" have great poignancy. The dance, choreographed by Warren Adams, sustains and supports the characterization and advances the story.

The first part of of the play follows traditional devices of an oriental tale. A young prince is being groomed for the throne as an aging king rules ineffectively amidst homicidal palace intrigue, Peripheral characters with names like "Slow, Painful Death" and "Swift, Violent Death" add to an Arabian Nights atmosphere. But this Scheherazade, in the guise of Oroonoko's love interest, the Princess Imoinda (Toi Perkins), has not volunteered to bring down the destructive king. She is brought to the palace on the evening of her wedding, and her new husband is paralyzed by loyalty to his king and Imoinda is forced into a slavery within her African kingdom mirrororing her slavery in the second act in the hands of the colonials. Thus this Scheherazade cannot find the words to fend off the horrors of the palace. (A caveat: the royal bath scene here is particularly harrowing and may not be suitable for younger audience members).

The subjugation of Imoinda in Africa illustrates Bandele's attempt to reach beyond the evils of slavery and show a complex society and complicit in the tragedy of the slave trade, just as Oroonoko is complicit in the eventual tragedy through his inaction. The stories Oroonoko (Albert Jones) tells himself are not the truth of his situation. but delusional narratives. The king's advisor, in a particularly Iago-like turn, is a dangerous character apparent to all but the blind Oroonoko. As Bandele's flawed hero he exhibits indecision, self-delusion, lack of vision — all recognizable traits looking through a Hamlet lens. The gift that this adaptation gives Oroonoko is the gift of eventual self-determination. Oroonoko, unlike Behn's character, takes his fate into his own hands.

The cast as directed by Kate Whoriskey is excellent. Standouts are John Douglas Thompson as the sly kingly advisor Oromobo and his worthy adversary in intrigue and narrative and the Lady Onola, played by Christen Simon. To further belabor the Shakespeare motif, the characters hint at the Friar and Nurse of Romeo and Juliet with Lady Onola in a role-reversal as the Friar. Her secret marriage of Oroonoko and Imoinda has disastrous consequences. However, Oromobo and Onola's farce-like ribald wordplay sit uneasily around the edges of the play where the tragic hands of fate, strikingly illustrated by scenic designer John Arnone's painted canopy hanging over the Duke's thrust stage.

Gregory Derelian brings the same menacing physicality to the role of Capt. Stanmore, a slave-ship officer, that he did to O'Neill's The Hairy Ape to such success last year. Graeme Malcolm, last seen on Broadway in Translations, is Byam, the deputy governor of the South American colony, struggling with native Arawark attacks. LeRoy McClain's Aboan is the servant and friend whose passion and decisiveness could have been his master's salvation.

David Barlow struggles somewhat with the one-dimensional role of Trefry, the sympathetic overseer acting on behalf of the Lord Governer of the slave plantations of Suriname. The ineffectual deputy gives many pronouncements of impending clemency, often to unintentionally comic effect. In Shakespeare' Caesar's ambitions were his downfall. Oroonoko had no such ambitions. All he wanted was his bride, and what her slave name, Clemene signfies —- mercy. "Is freedom, without the loss of lives, not worth accepting?" a character asks. In Behn's and Bandele's worlds, freedom would be accepted, but it is not offered.

|

Oroonoko Aphra Behn novella adapted by Biyi Bandele Director: Kate Whoriskey Cast: Ezra Knight (Akogun), Albert Jones (Oroonoko), LeRoy McClain (Aboan), Jordan C. Haynes (Laye), John Douglas Thompson (Orombo), Christen Simon (Lady Onola), Ira Hawkins (Kabiyesi), Toi Perkins (Imoinda), Gregory Derelian (Captain Stanmore), David Barlow (Trefry), Graeme Malcolm (Byam), Che Ayende (Otman). Scenic Design: John Arnone Costume Design: Emilio Sosa Lighting Design: Donald Holder Sound Design: Fabian Obispo Fight Director: Rick Sordelet Choreographer: Warren Adams Theatre for a New Audience, the Duke, 229 West 42nd Street, (646) 223-3010 tfana.org Opened 2/10/2008. Closing 3/9/2008 Tues.- Sat. @ 8 p.m., Sat. matinees @ 2 p.m. Sun. 3 p.m. Running time: 2 hr. 30 mins. One intermission. Tickets: $75. $10 for ages 25 and under Review based upon the 2/09/08 performance |

Try onlineseats.com for great seats to

Wicked

Jersey Boys

The Little Mermaid

Lion King

Shrek The Musical

The Playbill Broadway YearBook

Leonard Maltin's 2007 Movie Guide

Wicked

Jersey Boys

The Little Mermaid

Lion King

Shrek The Musical

The Playbill Broadway YearBook

Leonard Maltin's 2007 Movie Guide