SEARCH CurtainUp

LETTERS TO EDITOR

REVIEWS

FEATURES

ADDRESS BOOKS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

DC

NEWS (Etcetera)

BOOKS and CDs

(with Amazon search)

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

DC (Washington)

London

Los Angeles

QUOTES

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

Type too small?

NYC Weather

A CurtainUp Review:

A Lesson Before Dying

by Les Gutman

So live, that when thy summons comes to join

The innumerable caravan which moves

To that mysterious realm, where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou go not, like the quarry-slave at night,

Scourged to his dungeon, but, sustained and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.

---from "Thanatopsis" by William Cullen Bryant

The innumerable caravan which moves

To that mysterious realm, where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou go not, like the quarry-slave at night,

Scourged to his dungeon, but, sustained and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.

---from "Thanatopsis" by William Cullen Bryant

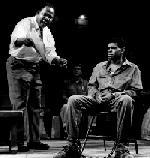

with A. Harpold behind (Photo: Susan Johann) |

A Lesson Before Dying is Linney's dramatic rendering of Ernest J. Gaines' award-winning 1992 book of the same name. (It has also been the subject of an HBO movie, in 1999.) The book is an elegant but harsh illumination of the search for grace and dignity before an innocent black man is put to death for a crime he did not commit; the play seeks to capture that story for the stage.

Jefferson (Jamahl Marsh) is the condemned young man, convicted -- because someone had to be -- by an all white jury. His (also white) defense attorney argued that he should not be put to death because he ought not be considered a man. It would be like electrocuting a "hog" for murder, he said. The year was 1948; the place was Pointe Coupée Parish, Louisiana. The description shocks us now (it shouldn't -- little has changed in the casualness with which we seem to put young black men to death). It jolted Jefferson as much as any current could have. He reacted by approaching his end as one would expect a hog to approach slaughter.

His elderly -- but strong -- godmother, Emma (Beatrice Winde), could not bear this thought. A religious woman, she could hope the Reverend Moses Ambrose (John Henry Redwood) might save Jefferson's soul, but she turned to the local plantation school teacher, Grant Wiggins (Isiah Whitlock, Jr.), begging him to teach Jefferson why he must die as a man.

But Wiggins was wrestling with his own stature. Having left the plantation for a college education, he returned, as he had promised, to teach the black students of this one-room school. He found his efforts at the school fruitless, leaving him to question his own worth. He wanted to escape the South with his love, Vivian (Tracey A. Leigh), herself a school teacher in town. No, she said. She was not prepared to leave, helping him instead to shape himself into the man he had to become to help Jefferson. However, it is the lessons he learns from the condemned man that succeed in exposing purpose in his own life.

This production is blessed with several sterling performances that ground it. Whitlock is magnificent, articulating with clarity the inner conflicts that plague Wiggins. Marsh, a young Rutgers graduate making his off-Broadway debut, lets Jefferson's character find his humanity sparingly, a sort of patient evolution that succeeds by never exploding. Redwood invests the unwavering foundation of the unschooled minister with simple integrity as well as a voice that seems to deliver the word of God first-hand. Winde's Emma is also finely drawn and portrayed, but the character of Vivian comes off forced and too glib; the scenes with her almost invariably seem too pat. I'm not convinced it's Ms. Leigh's fault; she appears to be the victim of the play's weakest writing.

Gaines' novel, which has become something of a contemporary classic, weaves a layered, organic picture of this community, revealing insight into its central story as well as an intricate understanding of the forces against which it develops. It's an achievement that the play does not -- and perhaps could not-- match. The staged result, while not without power, nonetheless feels like a Cliff Notes version of the novel, glossing over considerable essentials, finding resolutions that are dramatically desirable but not very satisfying, or accurate, if you believe the book. It also suffers in the translation from a narrative told by Wiggins.

Kent Thompson, who directed the original Alabama production, again does the honors here. He does so impressively, letting Linney's fast-paced and shifting story unfold clearly and with poignancy, if on occasion a bit more obviously than need be.

Marjorie Kellogg has designed a very effective set that evokes the courthouse storeroom in which much of the play takes place while efficiently setting up scenes at several other locations. All of the other design elements are also quite good, and the incidental music composed by Chic Street Man is perfectly suited without being predictable.

In the end, which is of course never in doubt, we are left with a feeling that brings to mind not so much the horror and injustice of this execution as the sense imparted by the end of Bryant's famous poem, quoted above. The novel finds a way to share in that poetry; the play does not.

LINKS

For a copy of the Gaines' novel, at a bargain price, click here.

| A LESSON BEFORE DYING

by Romulus Linney based on the novel by Ernest J. Gaines Directed by Kent Thompson with Stephen Bradbury, Aaron Harpold, Tracey A. Leigh, Jamahl Marsh, John Henry Redwood, Isiah Whitlock, Jr. and Beatrice Winde Set Design: Marjorie Bradley Kellogg Costume Design: Alvin B. Perry Lighting Design: Jane Cox Sound Design: Don Tindall Original music composed by Chic Street Man Running time: 2 hours with one intermission Original production of Alabama Shakespeare Festival Signature Theatre Company Peter Norton Space, 555 West 42nd Street (10/11 Avs.) (212) 244-PLAY Website: www.signaturetheatre.org Opened 9/18/2000 limited run, no closing date announced Reviewed by Les Gutman 9/19 based on 9/14 performance |