SEARCH

CurtainUp

REVIEWS

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

LA/San Diego

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

On TKTS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

NYC Weather

A

CurtainUp

Review

Havana Is Waiting

|

Home is that sentimental abstract place. Home is that yearning in your gut feeling.

--- Frederico. To his Cuban taxi driver Frederico observes that Sometimes this {Cuba} seems like home sometimes it doesn't. |

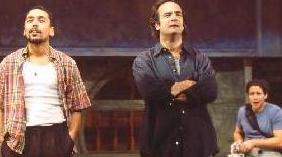

Felix Solis, Bruce MacVittie & Ed Vassalo

(Photo: Carol Rosegg)

|

Thomas Wolfe famously declared "You can't go home again", but in late 1999 Eduardo Machado proved him wrong. Sent out of Castro's Cuba on a Florida-bound "Peter Pan " flight at age nine, he dreamt of but never saw his Cuban home again. It took thirty-six years, but in 1999, as part of a cultural exchange program, he did go home again. While that return to Cuba was not permanent, it did help him to work through enough of his identity conflicts to finally consider becoming a US citizen.

Coinciding as it did with the beginnings of the Elian Gonzalez brouhaha, that emotionally restorative journey, also provided the underpinnings for Havana Is Waiting, the poetic and often comic saga of a flamboyant Cuban-born American-based writer who has obtained a visa as part of Castro's "family reconciliation" policy and, accompanied by an Italian-American friend, boards a plane for the country he left more than three decades years earlier. Sound like an autobiography? Well, it is.

Frederico is Eduardo's alter ego. The two other characters, his friend Fred and Ernesto, a Cuban taxi driver are Machado's fictional inventions to help him explore how the same troubling sense of belonging to two worlds but not fully to either pertains to national, political and sexual allegiances.

When Michael John Garcés directed an earlier version of the play at the Humana Festival in Louisville it was in a theater in the round. The director has done a beautiful job of adapting it to the Cherry Lane Theatre's smallish proscenium stage. Bruce MacVittie brings the right mix of toughness and sensitivity to the leading role. Judging from their current performances, Mr. Garcés did well to retain Ed Vassallo and Felix Solis, the original Fred and Ernesto, and also percussionist Richard Marquez to provide the sensuous Latin drumbeat.

Press reports indicate that the playwright has fine-tuned the script since my colleague Chris Whaley saw it in Louisville. The self-indulgences to which he objected have not vanished. The lyricism of the dialogue is at times overwrought (especially in the love scenes between the two Freds, whose issues often seem to belong in another play). There remain stretches, especially at the very end, that teeter on the verge of sounding like a Cuban-American social studies lecture.

For me Frederico's guilt about leaving Cuba simply doesn't hold water. A nine-year-old child can hardly be expected to be the captain of his own fate. I was troubled by the fact that Machado touches on his father's infidelity and the parents' subsequent divorce but never really connects this to his anger over their emigration. Also troublesome is the scene when the conversations with Ernesto turn into political debate and Frederico, without a moment's ambiguity divorces himself from being an American -- shades of Machado's statement in a NYTimes article about only now being ready to considerUS citizenship.

On the overall, I did find the text as juicy as the Latin drumbeat that punctuates it. Much of the dialogue is muscular and straightforward and some of the more poetic passages are quite moving. As for the Elian Gonzalez custody battle, it works. Machado lets Frederico's journey lean on it just enough to make the connection between the poster boy and the grown man wishing he had been reclaimed, but not so heavily that the play will be dated as the story fades in people's memories.

The best thing about Havana Is Waiting is that it takes all these serious issues -- lost homelands, identities and separated families -- but doesn't take itself melodrama-serious. Frederico's angst about going on the trip as expressed through his concern for his dog Stella (as in Stella from A Streetcar Named Desire), his hamming it up as Blanche while Fred focuses his everpresent video camera on him, macho Ernesto's self-conscious goodbye kiss at the airport (Ernesto, as played by Solis, is a gem!). . . these are just some of the funny touches that keep meolodrama at bay. Duality, you see, is not just part of Mr. Machado's national and sexual identity, but his playwriting style: street talk coexists with poetry; serious, issue-oriented themes with frivolity; and credibly moving scenes with passages of occasionally ludicrous excess.

|

Havana Is Waiting

(Originally When the Sea Drowns in Sand Written by Eduardo Machado Directed by Michael John Garcés Cast: Bruce MacVittie, Ed Vassalo, Felix Solis Percussions: Richard Marquez Set Design: Troy Hourie Costume Design: Elizabeth Hope Clancy Lighting Design: Kirk Bookman Sound Design: David M. Lawson Running Time: 2 Hours, including one 10-minute intermission Cherry Lane Theatre(38 Commerce St. (3 blocks below Christopher St., off Seventh Ave. South)., 212/239-6200- From 10/11/01; opening 10/24/01 Tuesday thru Friday at 8PM; Saturdays at 5PM & 9PM, Wed and Sundays at 3PM -- $55. $20/Student Rush, day of performance at BO Reviewed by Elyse Sommer based |