SEARCH

REVIEWS

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

DC

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

On TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

Writing for Us

A CurtainUp DC  Review

Review

Review

ReviewDeath and the King's Horseman

by Rich See

|

To prevent one death, you will actually make other deaths? Ah, great is the wisdom of the white race. -- Iyaloja, Mother of the Market

|

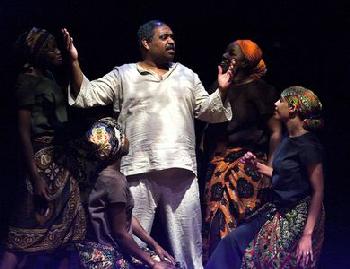

F. Harris with C. Ejuma, M. Changwe, M. Kemp and B. K. Asare-Bediako

(Photo: Ray Gniewek) |

Based upon true life events that took place during 1946 in British colonized Oyo, Nigeria, Washington Shakespeare Company's Death and the King's Horseman tackles a difficult subject with good results.

Wole Soyinka's writing is poetic, intense and requires a great deal of concentration from the audience. The playwright dislikes having his work defined as just a simple "clash of cultures" story and instead prefers to focus it as one man's struggle to fulfill his role to his tribe and dead king. As it is written, Mr. Soyinka's play about Elesin the Horseman examines a tribe/society's beliefs and how these are filtered into individual behavior and personal choices. It also is also a play about two clashing cultures and the surprisingly similar mindsets they share concerning duty and loyalty.

When Elesin's king passes away, he is -- by virtue of his birth and station -- required to kill himself and accompany his leader to the afterlife. (Similar to Western soldiers being led to die in a war that they did not choose to start.) When news of this tribal custom reaches the District Officer, Simon Pilkings, he decides to save the horseman from his fate by imprisoning him for the night.

Not entirely humanitarian, Pilkings chooses this action in order to keep any unpleasantness away from the colony during the visit of Britain's royal prince. In addition, he is offended by the custom and does not understand how deeply imbedded this aspect of life is within the Yoruba culture. In point of fact, Pilkings is not cognizant of any importance cultural traditions and beliefs may have to the people he is charged with overseeing.

Elesin, for his part, is demanding a new bride before he embarks on his death journey, which is a forboding of his weakening faith. Meanwhile his son Olunde has unexpectedly returned from England (where he has fled to attend medical school) to bury his father after the horseman's death ceremony. Things completely fall apart with tragic results when Pilkings has Elesin arrested. The District Officer's interruption of the ancient ritual reveals the doubt in Elesin's faith, the hypocrisy within Olunde and the other tribal members, and the prejudice inherent in Pilkings, his wife and the other British soldiers.

Director John Vreeke has devised a sweeping production that unfolds in unexpected ways on Misha Kachman's bare set. Mr. Kachman uses the entirety of WSC's staging area and has adorned its floor with African designs and added two raised dais. Brooke Kidd's choreography takes advantage of the space to create the African dances that permeate the play. And Ayun Fedorcha's lighting adds nuances to the actor's performances, while Erik Trester's projections produce an interesting special effect.

The sixteen-member cast keeps our attention throughout the show and offers some terrific performances. Felipe Harris' Elesin the Horseman shows the fragility of a man caught in a situation he did not expect to encounter. Towanda Underdue is an exceedingly strong Iyaloja, Mother of the Market. Ian Armstrong and Nanna Ingvarsson are sympathetic as Simon and Jane Pilkings, two products of the British Empire mentality. Frank Britton's houseboy Joseph shows a deferential attitude that belies the seething disgust he actually feels. Joe Lewis provides a humorous Sergeant Amusa. And Clifton Alphonzo Duncan's Olunde is a suave, intelligent man, who reveals little but says much.

With our world looking at how far respect should go in allowing various cultural and religious groups to practice their beliefs, Death and the King's Horseman is a cautionary tale. Washington Shakespeare Company presents an interesting production that not so subtly asks us all to examine our own preconceived ideas about life, death, strength, duty and tolerance.

|

Death and the King's Horseman

by Wole SoyinkaDirected by John Vreeke with Felipe Harris, Maurice E. Clemons, Barbara K. Asare-Bediako, Mwangala Changwe, Constance Ejuma, Letricia Hendrix, Micha Kemp, Towanda Underdue, Kamil J. Hazel, Joe Lewis, Ian Armstrong, Nanna Ingvarsson, Frank Britton, Richard Mancini, Nick Scott, and Clifton Alphonzo Duncan Set Designer: Misha Kachman Lighting Designer: Ayun Fedorcha Costume Designer: Genevieve Williams Sound Designer: Matthew Nielson Projections: Erik Trester Movement Choreographer: Brooke Kidd Fight Consultant: John Gurski Running Time: 2 hours and 10 minutes with one intermission A production of Washington Shakespeare Company Clark Street Playhouse, 601 South Clark Street, Crystal City Telephone: 1-800-494-8497 http://www.washingtonshakespeare.org THU - SAT @8, SAT - SUN @2; $22-$30 Opening 02/14/06, closing 02/12/06 Reviewed by Rich See based on 02/19/06 performance |