SEARCH CurtainUp

REVIEWS

FEATURES

NEWS (Etcetera)

ADDRESS BOOKS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

Los Angeles

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

On TKTS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

NYC Weather

Cobb

by Les Gutman

|

No man wants to be forgotten --- Ty Cobb, via Lee Blessing |

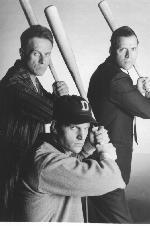

Ty's: M. Cullen, M. Mabe and M. Sabatino

(Photo: Kevin Fox) |

Blessing's approach is distinctive. After the exhaustive study of baseball on PBS (the series by Ken Burns), we're not pining for more reasons to hate this violence-prone racist whose achievements we love: baseball's first millionaire and seemingly permanent record-holder. But Cobb finds a fresh context in which to examine the man's interior life and the way in which he is remembered. If it causes us to consider our own penchant for romanticized nostalgia, that's not such a bad thing either.

Three actors portray Cobb at different stages of his life: as a young ballplayer (Michael Mabe), as a middle-aged businessman (Michael Sabatino) and as an old man at the threshold of death (Michael Cullen). They do not appear seriatim, as one might expect, but together, punchily engaging and confronting each other's evasions. It seems to be an argumentative version of one of those dreams in which we supposedly see our lives flash before our eyes. It's also a more theatrical version of the biographical monologue we so often see.

This play-dream is also inhabited by a fourth Cobb, one who's not likely to have manifested in Ty's subconscious. His real name is Oscar Charleston (Clark Jackson), but when he played baseball (in the Negro League), he was known as "the black Cobb." He haunts each of the white Cobbs obsessively, reminding of missed opportunities and John Rocker-esque embarrassments. It's easy to see what Blessing is trying to achieve with this character, but despite a fine performance by Jackson, its more of a diversion than an aid.

Different sorts of demons certainly did loom large in Cobb's world, chief among them Babe Ruth, whose popular successes tormented Cobb to the end. Matt Maraffi's simple set includes Ruth prominently among a backdrop of sepia photographs; Cobb spent much of his life unable to avoid the glare of similar ones. In baseball, which Cobb felt was his sport, he found but one flaw: it was a team game. He was prepared to yield the spotlight to no one.

Blessing posits Cobb's father left him ill equipped to stomach anything short of being on top. "Don't come home a failure," he warned him. In the end, Cobb comes off as neither a failure nor a hero. "Great lives cover great tragedies", he says, begging the question of whether either use of the adjective applies. That's probably as it should be.

Pictures of Ty Cobb always seem to feature a hard-posed, defiant lower jaw. It's interesting how these three actors -- the cocky Mabe, the meanly-determined Sabatino and the irascible Cullen, all quite good -- are able to capture this feature in its ascendency as well as descent. Propelled by Joe Brancato's energetic direction, they flesh out quite a reasonable portrait, neither exaggerated nor understated,

|

COBB

by Lee Blessing Directed by Joe Brancato >with Michael Cullen, Matt Mabe, Michael Sabatino and Clark Jackson Set Design: Matt Maraffi Lighting Design: Jeff Nellis Costume Design: Daryl A. Stone Sound Design: Faith Drewry >Running time: 1 hour, 15 minutes with no intermission A production of Melting Pot Theatre Company Theatre 3, 311 West 43rd Street, 3rd Floor (8/9 Avs.) (212) 279-4200 Opened April 17, 2000 closes May 20, 2000 Reviewed by Les Gutman 4/18/2000 |