SITE GUIDE

SEARCH

REVIEWS

REVIEW ARCHIVES

ADVERTISING AT CURTAINUP

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

New Jersey

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

A CurtainUp Review

Catch-22

|

They're trying to kill me.—Yossarian

|

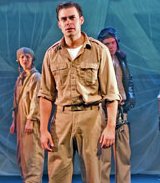

John Lavelle; with Christina Pumariega and

Chip Brookes in background.

(Photo: Richard Termine) |

This season, Peter Meineck's Aquila Theatre has risen to the challenge of dramatizing the novel, with mixed results. Meineck's adapted text is remarkably true to the spirit of the novel, and his direction surely captures the madcap reality of Heller's world.

Catch-22, the play, features John Lavelle as the central character — Yossarian, a bombardier stationed on a small island off the coast of Italy in 1944. Yossarian has decided he'd "rather die than be killed in combat." He fakes liver disease, insanity, anything to get out of combat, but all to no avail. The principal catch-22 is that if a serviceman is mentally disturbed he won't have to serve, but if he doesn't want to serve, obviously he's not insane.

Yossarian watches as most of his friends are killed in combat. He woos, wins and abandons several women. In the play's funniest scene, he fills in for a dying soldier who unfortunately succumbed before his family could arrive. The resulting dialogue between the grieving members of the family should become a comedy classic.

Yossarian has several nemeses: Milo Minderbinder, the corrupt mess officer who has turned the war into a private and very lucrative business for himself, all of the officers, who keep increasing his mission quota for their own personal advancement or avoid problems altogether by making themselves perpetually unavailable.

Catch-22 treads a fine line between comedy and tragedy, sometimes swerving into one realm and then back into the other. In the end, this play version is not quite successful as either. The problem is not so much the dramatization as the work it is based on. Heller's novel was non-linear and episodic. It was held together by a central idea, Heller's wonderful sense of the ridiculous and the eccentric characters that populate his remarkable world. This works well in the novel but not so well in the play.

Despite the enormous energy exhibited by the cast, often in multiple roles, and the fast pace of the action, this production seems to get mired in its own message. After a while the scenes become repetitive and the joke a little stale. The cast rolls onstage the skeleton or an airplane, sets up the beds in the hospital, places an inflatable raft in the middle of the stage, then engages in a bit of conversation for each scene. Yet nothing ever happens. And until the dramatic ending, nothing ever substantially changes.

Perhaps a novel can be built around a central tragic joke. But not a play.

|

Catch-22 By Joseph Heller Adapted and directed by Peter Meineck Cast: Mark Alhadeff, David Bishins, Chip Brookes, John Lavelle, Christina Pumariega, Craig Wroe, Richard Sheridan Willis Design: Peter Meineck Sound Design: Mark Sanders Movement: Desiree Sanchez Running Time: 1 hour, 20 minutes with one intermission Presented by Aquila Theatre At Lucille Lortel Theatre, 21 Christopher Street, between Bleecker & Hudson Streets) 212/279-4200. From 11/14/08; opening 11/23/08; closing 12/20/08 \ Tuesday to Saturday at 8pm, Wed, Sat and Sun at 2pm Reviewed by Paulanne Simmons November 23, 2008 |

|

REVIEW FEEDBACK Highlight one of the responses below and click "copy" or"CTRL+C"

Paste the highlighted text into the subject line (CTRL+ V): Feel free to add detailed comments in the body of the email. |