SITE GUIDE

SEARCH

REVIEWS

REVIEW ARCHIVES

ADVERTISING AT CURTAINUP

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

New Jersey

DC

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

Writing for Us

A CurtainUp Review

The Caretaker

|

I said to this monk, here, I said, look here, mister, he opened the door, big door, he opened it, look here mister, I said, I showed him these, I said, you haven't got a pair of shoes, have you, a pair of shoes, I said, enough to help me on my way. Look at these, they're nearly out, I said, they're no good to me. I heard you got a stock of shoes here. Piss off, he said to me.

---Davies |

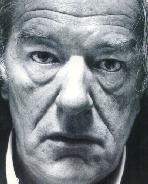

Michael Gambon

(Photo: John Haynes) |

Forty years after The Caretaker was first performed in London, comes this brilliant revival, directed by the multi-talented Patrick Marber, well known as a playwright, and starring Michael Gambon. Like Samuel Beckett's plays, nothing very much happens but somehow you are transfixed by the chemistry of the power play between the characters. I rejected the television version with Donald Pleasance as not very interesting, a lapse I can now ascribe to youth and foolishness but also because it is in the theatre that Pinter's characters grasp you by the throat and refuse to let go.

Pinter wrote The Caretaker in the cold autumnal months of 1958 whilst living in two rooms in Chiswick with his wife, Vivienne Merchant. In that house lived a man with a history of mental illness, who brought a homeless man to live with him. Of course what happens in the play is the result of Pinter's imagination, but these people were the starting point for his story. In the most unspeakably dilapidated slum flat, in a house in West London, Aston (Douglas Hodge) brings home the tramp Davies, (Michael Gambon). Aston speaks slowly and deliberately as if retarded and befriends Davies, offering him somewhere to live. Aston's brother, the altogether sharper, Mick (Rupert Graves) discovers Davies alone. Both brothers confide in the tramp, sounding out their ideas and both offer him the job of caretaker of their finished dream.

Gambon of course could read a computer manual out loud and hold my attention. To look at, he is broken down, his eyes heavily bagged, his hair dirty and greased down with a low parting to cover his pate. He holds his mouth open, his lower jaw gummy as if toothless. His clothes are unspeakably filthy. The long fingers of his large hands scratch his crotch and his behind. He shuffles along, dragging his feet. His accent ranges, quite deliberately -- a touch of Irish, a touch of Cockney, Polish, Welsh, all contributing to this enigmatic man who tells us repeatedly that he has to get to Sidcup to get his papers. (Sidcup is a suburb of south east London, bordering Kent, maybe three hours and several changes of bus away from Chiswick.) Some of the humour is in the ironic fastidiousness of this man, whose outward appearance belies this: He rejects the shoes offered him by Aston because he's uneasy at wearing brown laces with black shoes. He prefers drinking Guinness out of a thin glass rather than a thick jug. He preens himself in the velvet smoking jacket of the English upper classes. His racism gives him people to despise, who he sees as lower than him in the pecking order.

The pasty white, endearingly slow Douglas Hodge seems not to have a nasty bone in his body. One of the play's most poignant moments is when he describes his electro-convulsive therapy in a psychiatric hospital. His life centres around carpentry tools and the shed he would like to build but we feel he never will. His performance as a simple soul is very good. By contrast in character, Rupert Graves' slick Mick -- good looking, a sharp dresser with grey snakeskin pointed toe shoes -- starts aggressively towards Davies but eases into almost friendship as he talks about his plans to develop the property. Mick's litany of London place names has a surreal quality.

This play is about power games and it is in the shifting delicacy of the balance that Pinter's naturalistic dialogue excels. When they snatch a bag of old clothes from each other, we see a compelling physical manifestation of the power structure. All three characters have this simmering unpredictability, a volatile aggression and we as the audience do not know when to expect it.

Rob Howell's set is perfect: peeling wallpaper, plaster exposed to the wooden lathe, bare floorboards, detritus, sticks of furniture, old cardboard boxes, piles of newspapers, a bucket suspended from the ceiling to catch the rain water; oh and yes, a small golden Buddha. Patrick Marber's direction is imperceptible, as great direction is, and special. You leave convinced these people were real.

Although it is only November, I think this has to get my play of the year award and Michael Gambon, the actor of the year. If I were a New York producer I would be booking it for a Broadway theatre.

| THE CARETAKER

Written by Harold Pinter Directed by Patrick Marber Starring: Michael Gambon, Douglas Hodge, Rupert Graves Design: Rob Howells Lighting Design: Hugh Vanstone Sound Design: Simon Baker for Autograph Running time: Two and a half hours with two short intervals Box Office: 020 7369 1731 Booking to 3rd February 2001 Reviewed by Lizzie Loveridge based on 16th November 2000 performance at the Comedy Theatre, Panton Street, London SW1 |

6, 500 Comparative Phrases including 800 Shakespearean Metaphors by CurtainUp's editor.

Click image to buy.

Go here for details and larger image.