SITE GUIDE

SEARCH

REVIEWS

REVIEW ARCHIVES

ADVERTISING AT CURTAINUP

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

New Jersey

DC

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

Writing for Us

A CurtainUp Review

The Brothers Size

|

All my life I carry your sins on my back.—

Ogun You don't make no friends in the pen. What you know?— Oshoosi. |

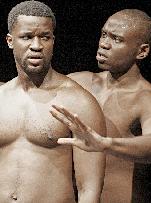

Gilbert Owuor as Ogun and Brian Tyree Henry as Oshoosi

(Photo: Michal Daniel) |

The play's imaginative blending of West African storytelling, music and movement with a contemporary story told in African-American vernacular is both impressive and at times compelling. Director Tea Alagic makes the intertwining of ancient technique with modern themes seamless and convincing. Yet there's something flat about this 90-minute narrative. And that something, unfortunately, has much to do with the play's very conception.

The Brothers Size tells the story of two brothers, the hard-working, upright Ogun (Gilbert Owuor in a tender and touching performance) and his ne'er-do-well brother, Oshoosi (the funny and heartbreaking Brian Tyree Henry). Oshoosi has just returned from prison, and Ogun insists his brother work for him in his auto mechanic shop and manage his life responsibly. Oshoosi, does his best, but he is haunted by his past and led astray by Elegba (Elliot Villar), a sly and cynical criminal he met in prison.

Jonathan M. Pratt accompanies the action with effective and dramatic drumming. In order to make The Brothers Size work within his dramatic structure, however, McCraney had to abandon some of the most basic rules of theater, the rules that ask playwrights to show and not tell, and to make the back story implicit rather than explicit.

The stories told in West African myths were tales of daring, adventure and trickery. McCraney's story is a psychological drama. It only works when the audience knows about the brothers' past — how Ogun took care of Oshoosi after their mother died, how Ogun always felt responsible for Oshoosi and his troubled life, how frightened Oshoosi was in prison, how he longed for his brother.

Within the framework of The Brothers Size most of the story, both past and present, can only be told in long monologues. The action is mostly offstage and related as memory. No matter how gifted the actors (and they are all extremely gifted) this is not the stuff of drama.

McCraney has the insight and skill necessary to mix moving poetry with bawdy comedy. At one moment Oshoosi graphically demonstrates his sexual exploits, the next he's talking about his loneliness and terror. There's a rhythmic fullness to the language that can become almost hypnotic at times. This is enhanced by choreographed movement and ritualized action totally in keeping with our ideas about African storytelling. However, the repeated use of the "N" word is a constant reminder that this is not really an African story and the brothers do not live in a village populated by farmers and led by a tribal chief.

The contrast between the mythic and the vernacular was most probably conceived as a unifying and driving force of the drama. But it can also be jolting and disruptive, breaking the mood and exposing the artifice. Only a willful effort to suspend disbelief makes it possible to get back into the story. Nevertheless The Brothers Size has many wonderful moments; Ogun and Oshoosi's rendition of Otis Redding's "Try a Little Tenderness" is one of them. And the ending is searing and beautiful.

They say you can't make an omelet without breaking eggs. In the case of The Brothers Size, this meant stepping outside some of theater's most cherished conventions. If McCraney had chosen a different story to tell, he might have been much more successful. As it is, one can applaud the effort and still remain skeptical of the result.

|

THE BROTHERS SIZE By Tarell Alvin McCraney Directed by Tea Alagic Cast: Gilbert Owuor (Ogun), Brian Tyree Henry (Oshoosi), ElliotVillar (Elegba) Scenic Design: Peter Ksander and Douglas Stein Costume Design: Zane Pihlstrom Lighting Design: Burke Brown Original Composition: Vincent Olivieri Percussion/Additional Composition: Jonathan M/ Pratt Running Time: 90 minutes without intermission The Public Theater The Public Theater production in association with The Foundry Theater,425 Lafayette Street,. (212) 967-7555, www.publictheater.org From 10/23/07. Opening 11/07/07. Closing 12/23/07. Tuesdays at 7 PM; Wednesdays thru Fridays at 8 PM; Saturdays at 2 PM and 8 PM; and Sundays at 3 PM and 7 PM. Tickets: $50. $25 Student rush in advance (1 per ID) at the box office; also a limited number of $20 Rush Tickets sold an hour before curtain at every performance e to the general public (Two per person, cash only). , Reviewed by Paulanne Simmons at Nov. 3 press review |

Try onlineseats.com for great seats to

Wicked

Jersey Boys

The Little Mermaid

Lion King

Shrek The Musical

The Playbill Broadway YearBook

Leonard Maltin's 2007 Movie Guide

Wicked

Jersey Boys

The Little Mermaid

Lion King

Shrek The Musical

The Playbill Broadway YearBook

Leonard Maltin's 2007 Movie Guide