SITE GUIDE

SEARCH

REVIEWS

FEATURES

NEWS

Etcetera and

Short Term Listings

LISTINGS

Broadway

Off-Broadway

NYC Restaurants

BOOKS and CDs

OTHER PLACES

Berkshires

London

California

New Jersey

DC

Philadelphia

Elsewhere

QUOTES

TKTS

PLAYWRIGHTS' ALBUMS

LETTERS TO EDITOR

FILM

LINKS

MISCELLANEOUS

Free Updates

Masthead

Writing for Us

A CurtainUp Review

The Brig

|

Sir, prisoner number three requests permission to cross the white line, Sir— The Brig

|

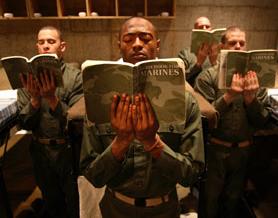

Albert Lamont, Jeff Nash, Isaac Scranton, and John Kohan

in The Brig

|

It was May 1963, and the Living Theatre, one of New York's foremost avant-garde companies, was producing Kenneth H. Brown's The Brig in the group's performance space at 14th Street and Sixth Avenue. But as so often happened with Julian Beck and Judith Malina's Living Theatre, it had aroused the ire of the U.S. government (the couple had not paid their taxes), and their landlord, possibly disliking theatre artists, especially theatre artists who disdained laws of various sorts, joined with the government to shut the place down.

Neither the landlord nor the Feds had reckoned with the determination and the anarchic, if pacifist, principles of the Living Theatre. On the night that the Becks were locked out, the audience ignored the barred door, climbed over the roof and entered the performance space through the windows, to watch one last, illegal presentation of Brown's hellish vision of a Marine Corps prison. After that, the production moved briefly to the Midway Theatre on West 42nd Street, to perform on New York's most famous decaying thoroughfare. The following year, the Living Theatre decamped to Europe, where government, for a while, was more tolerant. They would not return to the U.S. until later in the 1960s.

Forty-four years after that first production of The Brig, the peripatetic company has yet again found a new home, fittingly on the Lower East Side, which may be the last outpost of avant-garde theatre in Manhattan. And once again Malina has directed it(Beck, whose original design for the production is largely duplicated, died in 1985).

In the small basement theatre on Clinton Street, audiences look down on a reconstruction of a Marine prison. First we see barbed wire, then beyond that a high chain-link fence, and at the rear of the stage a row of bunk beds containing sleeping men. White lines on the floor mark doorways. A couple of guards dressed in khaki uniforms lounge against a pillar, until white lights snap on and, whether because of their whim or the rule book, they wake the prisoners.

The men are not allowed to speak to each other—they can only request permission to cross a white line or answer a guard's question. They must jog when going anywhere (no walking allowed). Infractions win them a punch in the gut. During the course of the two acts, the men dress and undress, swab the compound, read a Marine manual while standing at attention. One of them loses it and gets put in solitary, forced into a straitjacket, and carried out on a stretcher. By the end of this horribly restrictive day-in-the-life, one prisoner has been released for good behavior, another has arrived to take his place.

In 1963, audiences sympathetic to the Becks' anarchic politics were understandably repelled by the dehumanizing treatment Brown depicted. (At the time, the Marine Corps claimed that such treatment of prisoners had gone out of style in the early 1950s). But in 2007, after the conduct of American soldiers at Iraq's Abu Graib prison and the conditions under which prisoners exist at Guantanamo, Brown's play, and Malina's staging, feel tame. To be sure, one still cringes to see grown men forced to endure a boring, repetitive and physically exhausting regimen. But one also has to wonder why Malina chose to stick with her original concept rather than ratchet up the terror a few notches. At times the guards seem almost kind. Even their moments of physical punishment lack force and conviction. Human nature, we know, is much crueler than what Malina has staged.

But demonstrating physical cruelty is not Malina's goal. According to her program note, she is more intent on depicting how a certain kind of discipline and "training to obedience. . .suppresses free will." She is not interested in presenting physical torture so much as the absurd rules that lead some human beings to behave inhumanely and others to accept that inhumanity without fighting back. Toward this end Malina's new production is more successful. Watching the prisoners perform their meaningless tasks with rigorous precision—watching them smoke cigarettes on cue, line up to go to "the head" only when allowed, staring front and unable to speak unless spoken to—one is both fascinated and horrified by the rules people invent to curb other people's freedom.

| The Brig By Kenneth H. Brown Directed by Judith Malina Cast: Johnson Anthony, Gene Ardor, Kesh Baggan, Steven Scot Bono, Brent Bradley, Brad Burgess, John Kohan, Albert Lamont, Jeff Nash, Bradford Rosenbloom, Jade Rothman, Isaac Scranton, Joshua Striker-Roberts, Morteza Tavakoli, Evan True, Antwan Ward, Louis Williams Designed by Julian Beck & Gary Brackett Running Time: 2 hours and 15 minutes, with 1 intermission The Living Theatre, 21 Clinton Street,(212) 792-8050, www.livingtheatre.org/ Thu tp Sat at 8pm; Sun at 3pm Tickets: $30; Pay What You Can on Thursdays From 3/15/07 to 6/03/07; opening 4/26/07 Reviewed by Alexis Greeene on May 17th |

Easy-on-the budget super gift for yourself and your musical loving friends. Tons of gorgeous pictures.

Leonard Maltin's 2007 Movie Guide

At This Theater

Leonard Maltin's 2005 Movie Guide

>

>